Turing's Hammer - Computation and Chaos

Do you ever get the feeling that there is some universal structure underpinning reality? It is easy when staring at the night sky to feel entwined with the cosmos and the bigger picture. Sometimes it feels as if it is on the tip of our tongues. Very rarely, we are afforded a glimpse into the enigmatic machinery that drives existence.

Recently, I have been exploring the conceptual link between abiogenesis and the notion that sentience and computational structures can arise naturally as a consequence of the logical underpinnings of reality. Following is a roadmap along my journey to this point and the fascinating links between disparate subjects that I have come across as a result. I hope that they might provide a similar amount of excitement to you as they have for me.

The Beginning

This semantic journey began back in High School when my friend implored that I pick up a copy of a veritable tome “Gödel, Escher, Bach”. I couldn’t have predicted how that book would transform my notion of self or my thoughts towards an existential framework to embed my understanding of life, but it suffices to say that work has shaped the lens which I view most of my philosophy through.

Given the incredibly broad scope of the book, it is difficult to explain, in short at least, what its key message is. GEB is one of those philosophy books that makes an attempt to explain the machinations responsible for sentience, life, and the structure of meaning. It is an epistemological journey that weaves the work of Kurt Gödel (a brilliant mathematician credited for proving the limitations of logic itself), M.C. Escher (a graphic artist with a keen mathematical intuition for recursion and beauty but with no formal training), and Johann Sebastian Bach (whose musical compositions and fugues contained intricate recursive structures akin to Escher’s paintings). What makes GEB stand out from a sea of similar spiritual works is the formal treatment of the subjects at hand. Much in the way the abstract nature of Zen abets Kōans to guide personal discovery, GEB leads the reader through many thought experiments that give flashes of insight on the nature of self, biology, semantics, and the recursive nature of being. It is one of those books that you might have to read 20 pages at a time and wait a week or so for the conclusion it was leading you towards to manifest (sometimes suddenly when laying in bed or on a hike). When I explore new topics, I find myself finding the teachings of GEB leaking through the cracks of most concepts. Ever since my encounter with that book, I have been convinced on many occasions that there are easter eggs hidden in our reality waiting for us to find them.

Abiogenesis

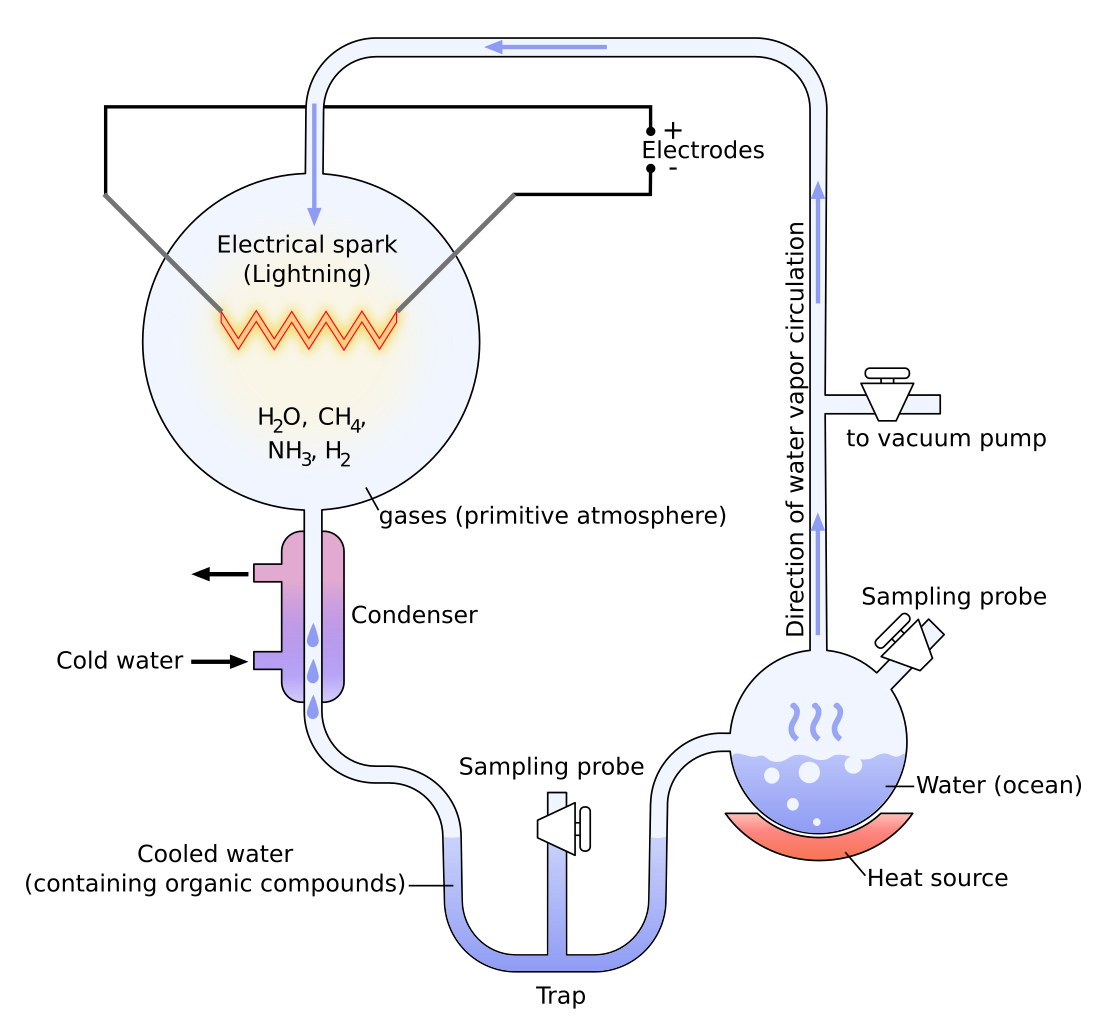

When discussing the origin of meaning and sentience, the discussion will inevitably drift towards philosophy of creation. There are many hypotheses for how life arose from inorganic material (abiogenesis), but one of my favorite explorations on this topic is the Miller-Urey Experiment wherein researchers created a closed-system that contained base elements required for life (Water, Methane, Ammonia, and Hydrogen) and a means of perturbing that solution to see what would happen. The perturbation involved boiling the solution, running the steam through an electric spark gap, condensing the steam, then recirculating the condensate back into the original reservoir.

The researchers found that, after a day of operation, 11 out of the 20 essential amino acids that create the building blocks for organic chemistry as we know it were created spontaneously in this closed system. The conclusion was that lightning, geothermal activity, and the presence of these common compounds could have paved the way for the first organisms on Earth.

Several variations of this experiment have been performed since and confirm under multiple chemical scenarios that amino acids essential to organic matter apparate from these stochastic processes that existed early on our planet.

But Why?

We have established that the building blocks for life are a structure that arise naturally in different chemical scenarios. So what? Even if we have that, why are biological structures the eventual output of the physics that govern our universe? This question is, of course, much harder to answer. The key to understanding this question may come down to one of the most fundamental and brutal laws of our universe: the 2nd law of thermodynamics:

“[T]he total entropy of an isolated system can never decrease over time, and is constant if and only if all processes are reversible.”

For starters, entropy is generally a measure of the amount of states a system can have given a macroscopic state of the system as a whole. For instance, there are billions of ways a small amount of gas might be at a temperature 70 degrees. Entropy is inexorably linked to the concept of energy, and describes how energy is dispersed at a given temperature. The gist of the 2nd law is that entropy is bound to increase in a closed system and everything, including the universe itself, is heading towards a concept known as Heat Death. The stars will all eventually burn out, and all matter will eventually decay into its lowest possible energy state. The inevitable conclusion is that matter is heading towards a global average, and structure will eventually decay from existence.

But, then, how does that explain life? Life spontaneously organizes into very regular structures. The human body is so complex that we still only have a basic grasp of some of its most fundamental systems. Life is a popular counter-example to the theory of entropy increase, since life inherently produces islands of lower entropy (equated here with complex structure, thus less micro-states explaining the same macro-phenomenon). The key takeaway in this context is that life (while having much lower entropy than its surroundings) is actually very efficient at increasing entropy as a whole. The Earth is far from a closed system, and the vast majority of energy dispersed on Earth comes from the sun. If you were to close off the earth from all external energy sources, you could envision that life would decay quite rapidly and entropy consequently would increase at an alarming rate.

Think, for a moment, that the 2nd law of thermodynamics is a goal of the universe. If the universe were to optimize for this goal, if not only because that is the nature of its reality, then it would make sense that structures efficient at increasing entropy would be a natural “conclusion” of this process.

To make this less hand-wavy, there has been considerable research on this topic. An incredibly useful application of this philosophy is the detection of extra-terrestrial life. One of the main goals of exploring neighboring planets like Mars is to see if life ever existed there, and if so in what form? A sticky topic in this goal is the definition of life. Alternate models for biology have been founded by replacing carbon with silicon, and it is easy to ask the question “what if life elsewhere is nothing like the biology we know here?”. Entropy turns out to be a very useful context in which to frame life as a consumer of negative entropy via Information Metabolism. It turns out using mathematical techniques like fractal analysis to discover differentials in entropy given an environment, we can detect life without needing to subjectively label something as organic or inorganic.

Complexity and Entropy

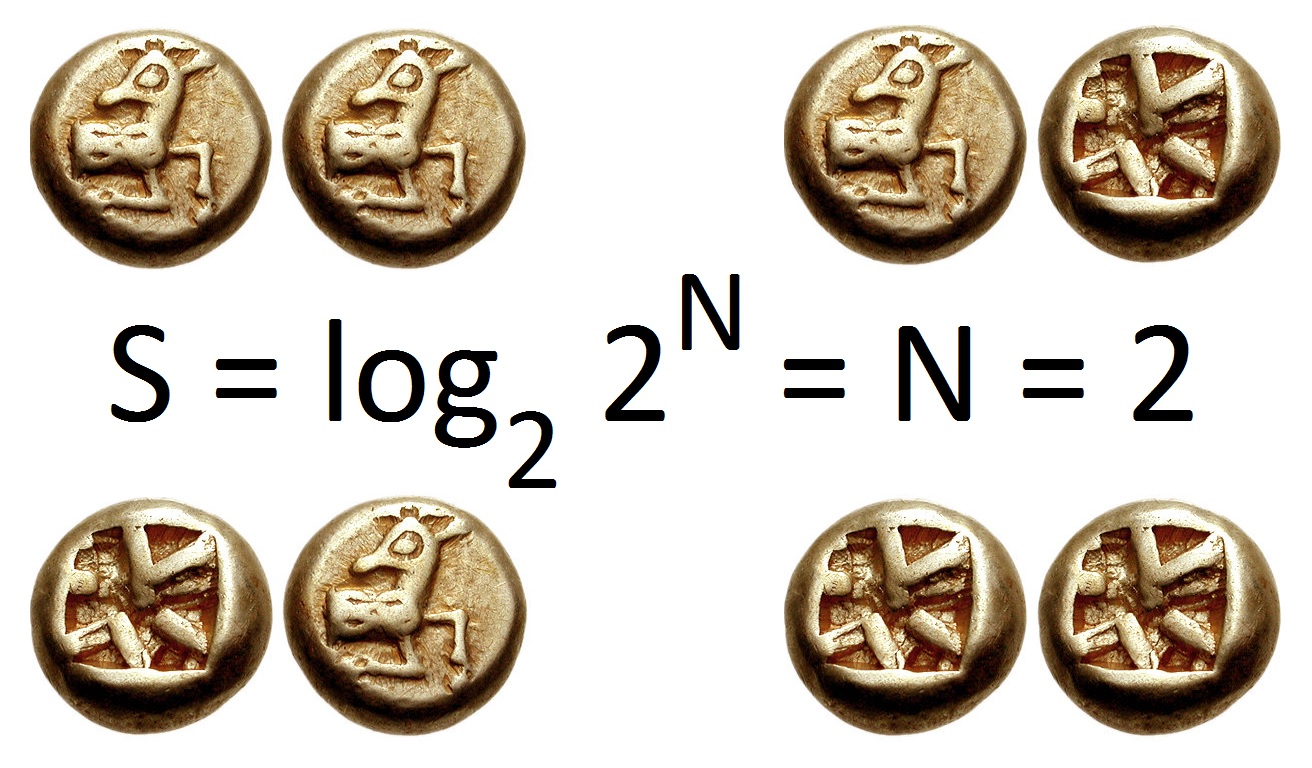

You might realize that the term “complexity” is tossed around in concert with entropy. This is where we start to blur the lines between computation, information, physics, and biology. An alternate definition of Entropy is Shannon Entropy, which is a “20 Questions” approach to describing the states of a system. Simply put, the Shannon Entropy of a system is the amount of yes/no questions (expressed commonly as “bits”) you have to ask before you are 100% positive you know what is being talked about. The Shannon entropy of a coin-flip is then one bit, 2.58 bits for a six-sided die, and less for a loaded six-sided-die. Another factor worth mentioning is that Shannon Entropy represents the average amount of bits required to describe a system’s state, not just one of its states.

Complexity, on the other hand, is a measure of exactly how much talking you must do in order to describe a given state of a system. In information theory, a common measure of complexity is Kolmogorov Complexity which is the length of the shortest computer program that produces the state in question. It is normally framed within the context of Lambda Calculus (which lets you represent computer programs in the most terse and mathematically rigorous form possible). For example, given a picture you took on your phone, the Kolmogorov complexity of that image would be akin to the smallest file you could compress it into without losing any detail.

A fascinating consequence of defining complexity in this way is that, in general, you cannot form a heuristic for finding the Kolmogorov Complexity of arbitrary data. That means that it is impossible to create a program to compute the Kolmogorov Complexity of any string of information. This result is a consequence of many of the same limitations of logic itself that lead to undecidable questions such as The Halting Problem, The Continuum Hypothesis, and Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems.

Under the definition of Shannon Entropy, entropy is the expected value (think of average) of the Kolmogorov Complexity of the system being measured. More simply stated, entropy is a measure of average complexity of a system. This is conceptually sufficient for my post on entropy here, but for further justification there are wonderful papers that have been written on this topic. Thus it makes sense to talk about complexity when speaking of entropy, or vice-versa. It is also important to not conflate the two, as they are describing different measures of a system.

At first, it seems nebulous how this new information theoretic definition relates to the physical definition we use in thermodynamics. After all, if these are different concepts, why talk about them? It turns out that Shannon Entropy and Thermodynamic Entropy are roughly equivalent, which is one of the first “bridges” so to say between the conversation about abiogenesis and the topics of information theory (since abiogenesis can be framed in terms of thermodynamic entropy).

On Computability

To connect the concept of abiogenesis and the Miller Urey Experiment to a hypothesis on the natural origin of computational structures, I first have to describe what I mean when I say “computational structure”.

The most basic model for a computer is perhaps the Turing Machine, named after its creator Alan Turing. The Turing machine is a mathematical description of a device capable of taking a program as input, running that program, and producing output from that program. The computer you are reading this post on is a very advanced and optimized version of this simple concept, and all computers today (save for quantum) operate on its principles.

To say that a problem is computable is equivalent to saying that a program exists that can be run on a Turing Machine and that program will eventually terminate and yield the answer to that problem as output. A machine that is equivalent to a Turing Machine is said to be Turing Complete. What is fascinating about Turing Machines is that the problem “given this program, decide whether or not it will terminate when run on a Turing Machine” is undecidable, which is to say that no program exists that can compute that answer. This is called the The Halting Problem (mentioned before when discussing Kolmogorov Complexity), and is dual to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems (which use similar logic to show some problems in math are undecidable). Maybe you are beginning to see just how connected all of these concepts really are.

Believe me, things get so much stranger.

Different Sides of The Same Coin - The Church Turing Thesis

Turing was an industrious fellow and, aside from independently deriving Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, also worked with Alonzo Church (the inventor of Lambda Calculus, a formal way to describe programs) to tackle a very important question: are there any problems you can solve that a computer can’t, and vice-versa? According to the thesis, surprisingly, the answer seems to be no. The thesis states that a problem can be solved in general (more formally, via an effective method) if and only if that problem is computable on a Turing Machine.

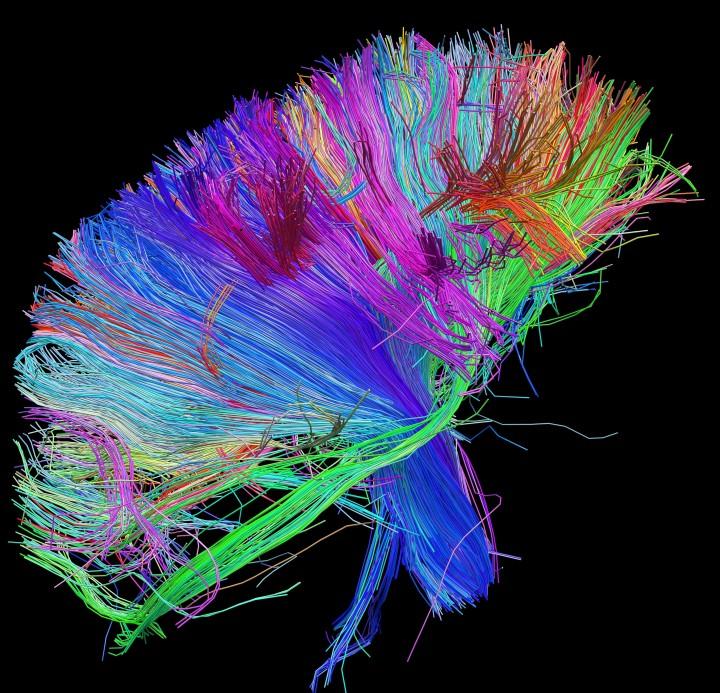

It is hard to express the gravity of that statement, let alone the philosophical implications such a fact would imply. The Church Turing Thesis is generally regarded to be true in much of academia, and is used as the basis for numerous concepts in theoretical computer science. Regarding the Philosophy of Mind, one could interpret the Church Turing Thesis as conclusive reasoning that the human mind, and cognition in general, is just another form of computer like a Turing Machine. The existence of a problem that acts as a counter-example to this argument is an open question, but for the sake of my exploration on this topic I would like to see what ramifications allowing this philosophy might lead to.

In short, this means that we may be able to probe an entropic theory on abiogenesis by investigating the possibility that a Turing Machine would form from the physics of the universe, or at least that we have some precedent to warrant further investigation on the connections between computation and life.

You also might be wondering why I am equating cognition and a theory of mind with abiogenesis, but keep in mind that even single-celled organisms have been capable of computation for millions of years. Biological computation predates the existence of neurons and is actively used by living creatures when developing a body. Even trees communicate and compute rudimentary decisions by using mycelium as a communication medium. I think that it is worthwhile to examine how computational structures arise out of the physics of a system.

Oops, All Turing Complete

Surprisingly enough, we already have quite a few examples of computation spontaneously arising in popular culture. Esoteric languages (programming languages designed to be hard to use) are a common hobby among programmers, but sometimes you don’t have to invent the esoteric language and ones can be discovered instead.

For instance, C++ templates were originally designed to provide an easier way to design generic function/class signatures that could accept a variety of types. Later, programmers found that you could chain and compose templates in a way that made them capable of computation. This accidental “feature” produced a language within a language.

One of my favorite examples is that, given a very carefully constructed deck, the card game Magic The Gathering™ is also Turing Complete. The rules of the game were never intended to form a computer, but you can absolutely run any program you desire by following them.

There are numerous examples of Turing Machines popping out of thin air, including PowerPoint, Border Gateway Protocol (this is what organizes large sections of the global internet system), and most notably here, Cellular Automata.

Cellular Automata - One Context To Frame the Genesis of Computation

Originally formulated by Stanislaw Ulam and John von Neumann, Cellular Automata are grid-based universes that operate on very simple rules. Later, John Conway (who unfortunately passed away this year) found a very specific Cellular Automaton named the Game of Life. The rules of the game are fairly simple. The game board is a square grid of cells, each one is either alive or dead. The game is played by advancing the board state iteratively by following some basic rules about whether a living cell will die, survive, or a dead cell will be born, or continue to be dead. A living cell with two or three neighbors will survive, and a dead cell with three neighbors will become alive on the next generation.

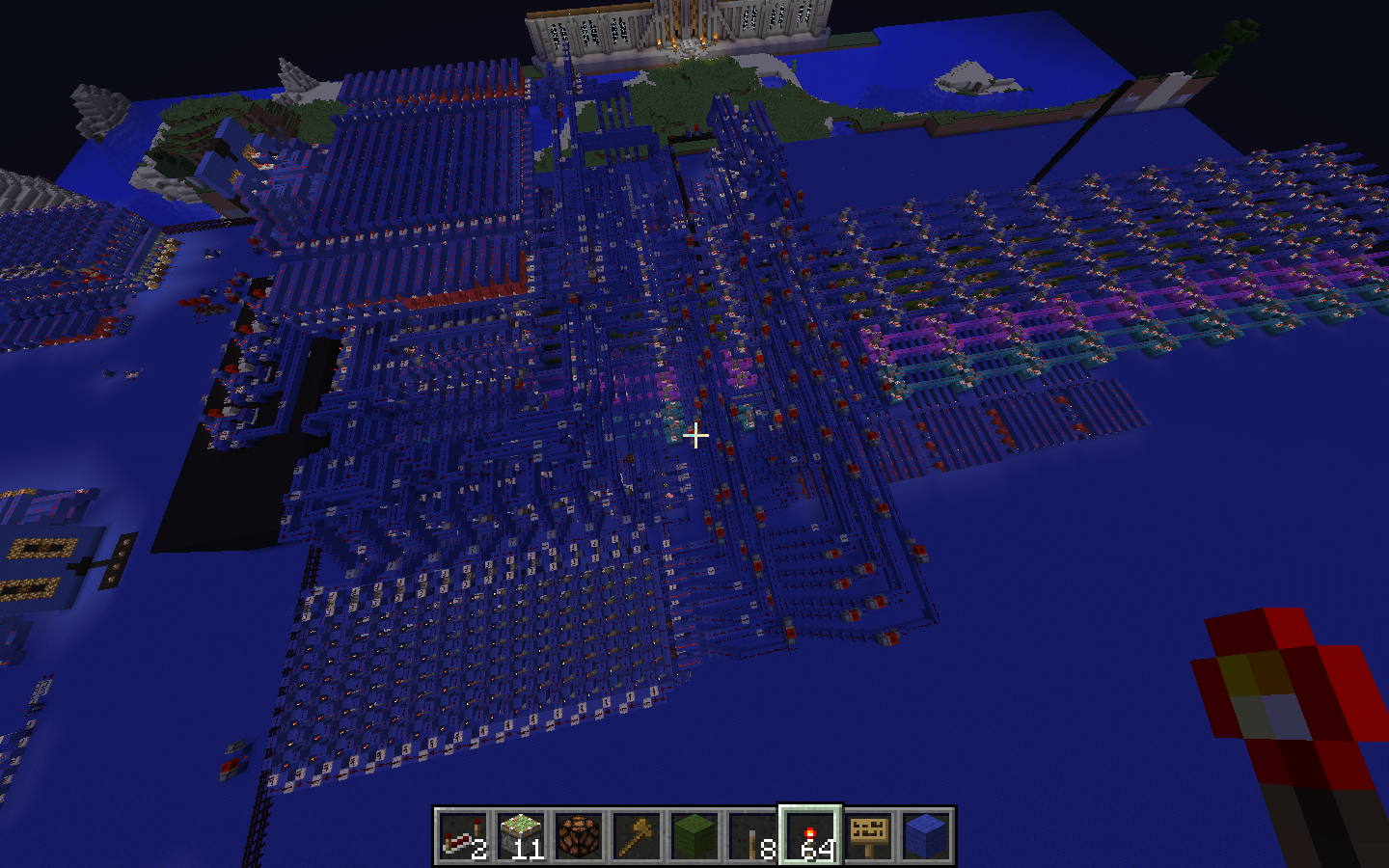

Even with these simple rules, Conway found that this game/universe supports persistent structures, the most famous of which is the Glider (a 3x3 construction of live cells that flies across the board). More surprisingly, researchers found that Gliders could be used to transmit information between structures on the grid, and logic could be triggered that would process that information. Eventually, someone created a Turing Machine in the Game of Life.

Again, Conway did not create the rules of the Game of Life with computation in mind, yet a computer did exist as a state in the system he invented. This is not an isolated phenomenon in Cellular Automata, either. Stephen Wolfram has spent his life researching what is possible with Cellular Automata. Even when the grid used for Cellular Automata is one-dimensional (instead of two-dimensional in the case of the Game of Life), researchers have constructed a Turing Machine using rule 110.

There are 262,144 Cellular Automata like the Game of Life, all of which are defined by how cells are born and how they die based upon the 8 neighbors that surround each cell in the grid. These are deemed “Life-Like Cellular Automata” and there has been some research on different rules in this space. For instance, the Anneal CA creates blob-like structures given a random starting state, whereas the Replicator CA produces many copies of initial patterns and explodes from an initial “seed” structure placed on the grid. Hours of fun can be had exploring these rules in the software Golly which has many of the structures I have discussed as examples you can load up and play around with.

It is easy to think of Cellular Automata as a toy invented by Computer Scientists and logicians, but it is remarkable what they are capable of. Already we have found that they can simulate fluid flow, heat transfer, gravity, flame, predator/prey models, annealing processes, structural properties, and much more. Stephen Wolfram posits that Cellular Automata might be a valid framework to describe the physics of our universe, and while a very bold claim, there is a lifetime of research backing his philosophy. I mention it here because it is important to realize that analysis of Cellular Automata could have deep implications relating back to our own universe, and shouldn’t be discredited as mere thought experiments.

The Experiment

Inspired by the Miller-Urey experiment, I wondered if there was some way to produce similar results with regard to computational structures in a given system. That is, given some space of systems, can you perturb the rules in a way that will eventually lead to a system capable of computation? Or, given one system, how might you find what a computer looks like in that world? The second question is much harder to answer, and is most likely the reason the discovery of new Turing Complete systems usually heralds some attention in academia. The first question, though, led me to what appears to be a valid way to measure the capability of a system for sustaining computational structures, and by extension of concepts like the Church Turing Thesis and works of Stephen Wolfram, life as well.

The initial challenge is finding a space of systems that is easy to canonicalize, which would make it easy to explore and probe for computational life. For instance, it would be intractable to try and explore every possible program that could be written for a modern computer due to the astronomical count of possible systems that can be run on our machines. Sure, software like PowerPoint has been proven to be Turing Complete, but I see no way of measuring that objectively without constructing an example by hand and pointing at it intently. Creating a program that constructs all possible programs for a modern machine, let alone manually searching the quintillions of possibilities, would take thousands of lifetimes of work.

Cellular Automata, on the other hand, are wonderful candidates for this exploration. Especially if we restrict ourself to the 262,144 Life-Like Cellular Automata, the search space is manageable if we can produce some heuristic for measuring the capability of each rule for producing a computer within its constituent universe. Plus, we already know that one of the rules (the Game of Life) supports computational structures and therefore a Turing Machine inside of the universe it creates. What other rules might do the same?

In order to fuel the search, I looked back to entropic theories of abiogenesis and the notion that life exists as islands of lower entropy and, in-turn, feeds on negative entropy to result in a net increase of total entropy in the universe. This concept is called information metabolism (explored by the Polish psychiatrist and philosopher Antoni Ignacy Tadeusz Kępiński). Due to the inexorable relationship between entropy and complexity, a search for instances mimicking life could also be mounted by observing the procession of complexity in a closed system instead of entropy. I posit that, like life, computational structures feed on negative entropy and in turn reduce the complexity of the environment.

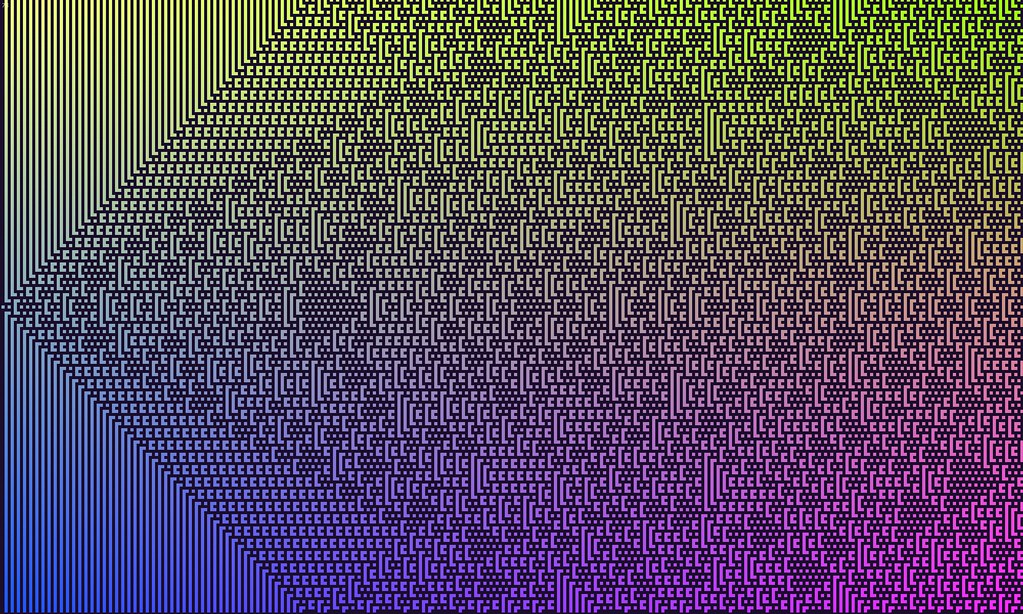

The next challenge is measuring the complexity of Cellular Automata as they proceed through their generations. Recall that Kolmogorov Complexity is comparable to compressing a piece of information into its smallest representation without loss. If you treat a Cellular Automata as a bitmap of pixels that are black when alive, or white when dead, then you can create a unique image from each state from the board of a Cellular Automaton. Then, using some optimized image compression algorithm, you could estimate the complexity of the board state by finding the file size after compression. In fact, it can be shown that properly chosen image compression correlates to Kolmogorov Complexity up to a constant (which means it is a decent measure).

I first looked at the JBIG2 compression algorithm as it is designed to compress bitmaps incredibly efficiently and losslessly. When compressing bitmaps, I found little to no difference between JBIG2 compression and PNG compression, and the latter was much more practical to use since JBIG2 is no longer in widespread use and software support is minimal.

Then, after writing a program to create Cellular Automata boards and run arbitrary rules through many generations, I created a simple Bash script that would go through bitmap image files of each iteration of the board and convert them to a lossless PNG representation (including PNG compression). A second bash script then listed the file size of each generation in order and wrote the results to a spreadsheet. For each Cellular Automaton I examined, I used a board of 500x500 cells (a quarter-million cells in total) run over 255 generations using 10 random initial board states (each cell had a 50% chance of starting alive or dead). This technique of starting with a random board state is fairly common when exploring the behavior of a Cellular Automaton.

To be honest, I expected the trend in compressed file size, and consequently the Kolmogorov Complexity of the Cellular Automata to be wildly noisy and I did not know what patterns to expect. I definitely did not expect the result to be what it was…

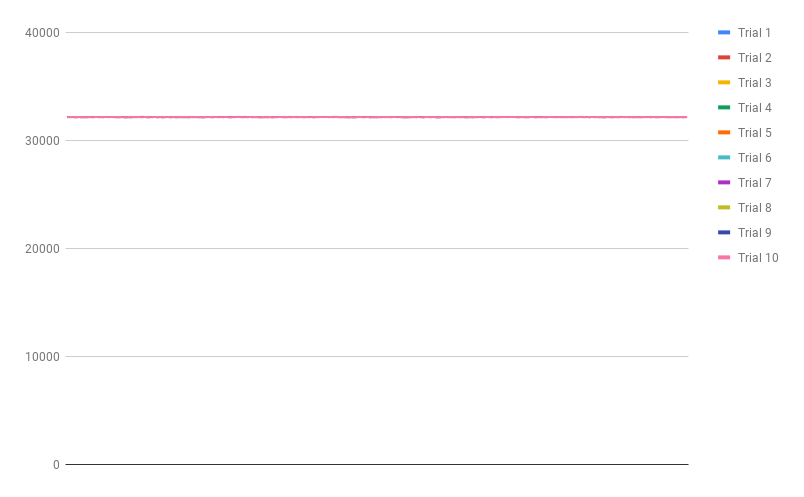

The progression of complexity for the Replicator Cellular Automata predictably stayed the same throughout all 255 generations in each of the 10 trials. This made sense, since the Replicator CA copies existing patterns, and thus starting with a very complex (fully random) image you would continue to get more of the same:

The board:

The Seeds CA is known for being an “explosive” system that, with almost any starting structures, will fill the board with patterns. Seeds quickly ate through complexity but appeared to over-shoot its long-term steady-state and asymptotically leveled off to a higher complexity within tens of generations:

The board:

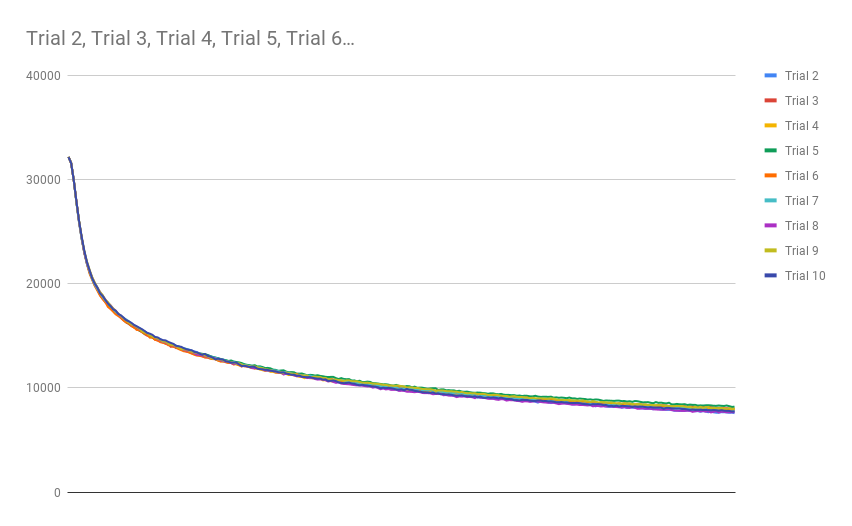

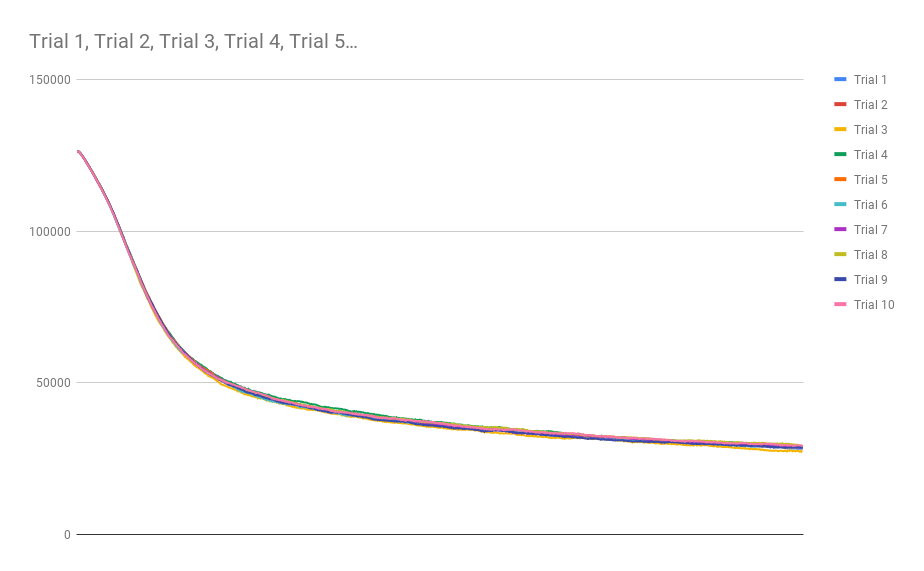

This is where things got more surprising. The Anneal CA, a system known for producing blob-like structures with smooth perimeters, ate through the initial high complexity and reached a low steady-state ending complexity after a hundred or so generations. More surprising than how readily this CA chewed through the complexity each trial was how smoothly it seemed to follow what appeared to be an exponentially decreasing curve:

The board:

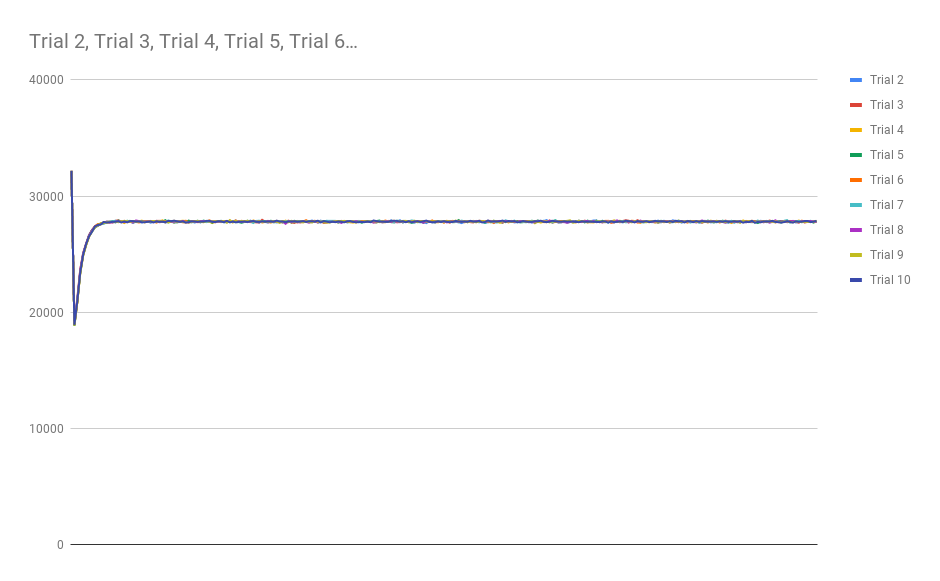

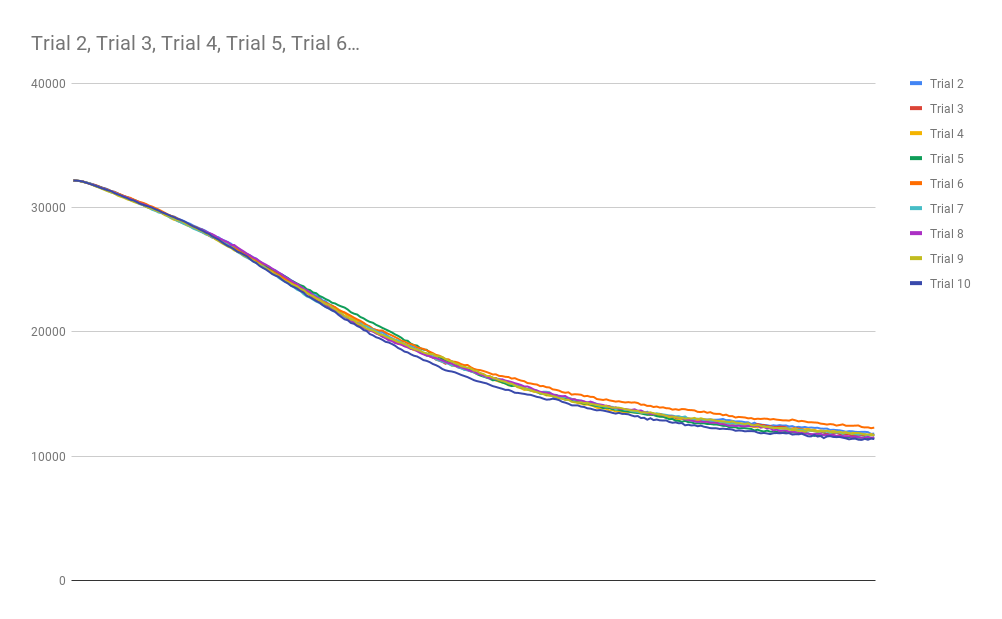

Of course, the real question was “How does Game of Life behave under this measure?” After all, Game of Life is known to be Turing Complete, so if this measure is to be worth anything in the search for similar systems, then it must produce remarkable results when measuring the Game of Life. I was pleasantly surprised to see that the Game of Life indeed did show some very different behavior than any of the previously described CA’s:

The board:

Notice how slowly the asymptotic steady-state complexity is approached with each trial of the Game of Life. Sure, Game of Life eats complexity much like Anneal, but it does it in a way that supports hundreds of generations before the system effectively reaches the asymptotic floor of complexity in the system. Even still, Anneal seemed to consume complexity at a somewhat slow rate. I have not yet found a glider structure in Anneal, but I wonder if computation is possible on the boundaries of the blob-like structures in that world.

There is a name for this concept of transition in complexity: The Edge of Chaos: the space between order and disorder. This concept shows up in many places, most importantly (here at least) as it pertains to Self-Organized Criticality, a phenomenon where complexity evolves as an emergent phenomenon of a system. Self-Organized Criticality typically occurs at the phase transition between two states of a system, and can be used to explain an alarming amount of physical and abstract phenomena.

Game of Life seems to allow many generations to exist in the phase-transition between high-complexity and low-complexity board states, which could indicate that it can sustain Self-Organized Criticality. This isn’t actually surprising. This was one of the traits the original inventors of Cellular Automata discovered in many of the systems they researched. To date though, I have not seen such an analysis on the procession of complexity and how it facilitates Self-Organized Criticality along the Edge of Chaos. I posit that systems capable of computation, or at least useful persistent structures like gliders that serve as building blocks for a Turing Machine will exist in systems that show a similar slow-burn on the available complexity in the system.

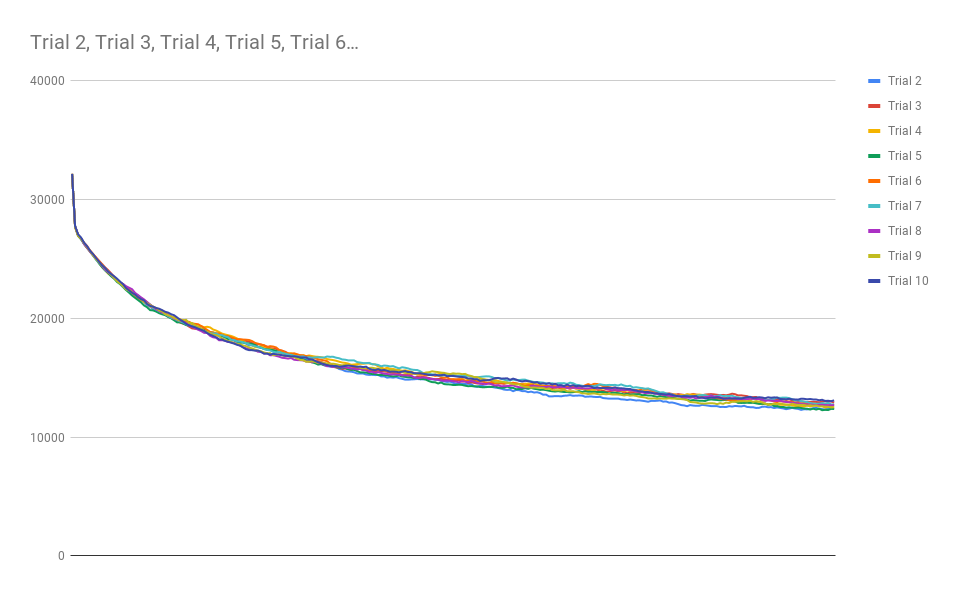

To test this hypothesis, I wanted to graph one more Cellular Automaton: Day and Night. This CA has the interesting property that a structure can be built from live cells surrounded by dead cells, or equivalently with the same structure of dead cells surrounded by live cells (thus the name). This CA supports gliders and complex structures, and (if I had to bet money) probably is Turing Complete. Here is the complexity graph that Day and Night produced:

The board:

It looks very similar to the Game of Life curve, save for the fact that this structure seems higher-order. That is to say that there is an inflection point in the monotonic asymptotic descent towards eventual steady-state complexity. Just for fun, I ran a much larger simulation of Day and Night with 1000 generations instead of 255 to see what would happen:

Further Thoughts

It seems there has been research adjacent to this topic, albeit that analysis was done on the computer simulation Tierra, and not on Cellular Automata. Regardless, they also found the complexity (as measured by a compression algorithm) to decrease with time, apparently violating the assumption that entropy must increase in a closed system. All life-like cellular automata I have analyzed so far seem to be monotone decreasing in complexity/entropy with each generation, but I wonder what rules might yield the opposite behavior. Even so, if a violation of increasing entropy heralds the capability for computational structures, how would that relate to our universe where entropy is bound to increase globally? Computers obviously exist in our universe, and thus are tautological results of the physics in our world.

The smoothness of these complexity curves are baffling and inspiring to me. Why are they so regular? What governs their shape? Can you predict the curve with any accuracy from the rules of the CA alone, or do you have to measure emergent behavior of the system as a whole? What type of curves are these? They appear to be exponential, oscillatory, or sigmoid in shape, yet there are so many curves that fit those descriptions that I would be naive to assume equality with some common functions without further justification.

I would like to analyze all 262,144 Life-Like Cellular Automata using this method and characterize them into groups based upon their complexity curve from random initial states. I wonder if it would shed light on rules that have not yet been explored yet that might have interesting or useful behavior. Perhaps the generation count from starting complexity to some band within steady-state complexity could be enough information to compress the entropic nature of a CA into one number.

And what if some CA’s do not have a long-term steady state? If so, what rules produce smooth curves like the ones described here, and which ones produce unexpected curves?

Lastly, I want to understand more about how these curves relate to information metabolism, and in turn how a similar analysis could be applied to studies on the definition and origin of life. If we find that the rules of our universe result in a similar slow-burn of available complexity, perhaps that could explain if life is a natural consequence of the physical laws that govern existence.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.