The Integers In Our Continuum

Artwork by my good friend Sophia Wood

Artwork by my good friend Sophia Wood

On Physics

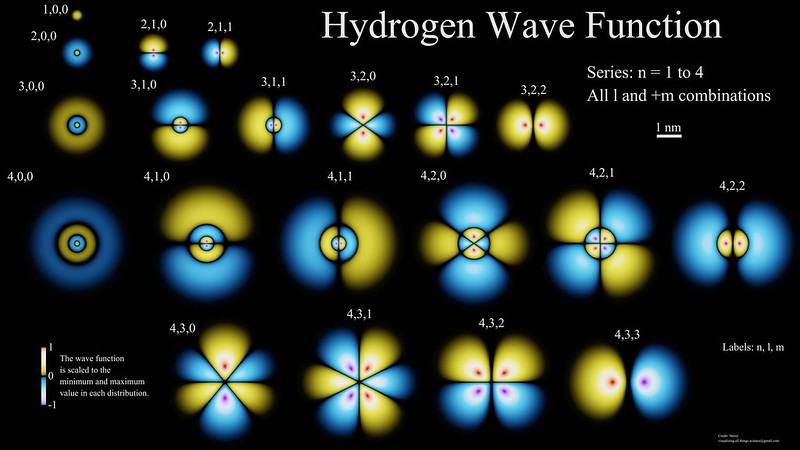

Recently, I was surprised to learn that the existence of quanta is not fundamental in our current understanding of physics. In other words, none of our models of physics begin with quantizations or discrete entities, they only end up with them after examination. David Tong, a mathematical physicist at the University of Cambridge, wrote a thought-provoking essay elucidating this ironic nuance in our models of physics. Quantum mechanics, for instance, begins with a continuous-valued wave equation describing the evolution of a wave packet from which measurements are taken by utilizing the convenient properties of Hilbert Spaces to allow proejction of the wavefunction onto another analytic object like a Hamiltonian. Many versions of this wave equation can be constructed given your baseline assumptions (Schrödinger for non-relativistic, Dirac for relativistic effects), but they all attempt to reckon some order from a continuous phenomenon. Despite beginning with a continuous picture, discrete quanta are a direct consequence of studying these equations.

Hydrogen wave function solutions (source).

Hydrogen wave function solutions (source).

Since discretization seems to emerge from solving wave equations, one may seek other fundamental sources of quanta. It may make sense to examine the degrees of freedom of a system to see if they yield canonically distinct entities. Most commonly, this can be interpreted as the independent axes of freedom in a model’s representation space. Still, this is not as canonical as one might hope as many potential models such as the AdS/CFT Correspondence where our models of quantum mechanics are dual to models that exist in higher dimensional ones. The holographic principle takes this in the other direction where entanglement on the two-dimensional boundary of a black hole may represent higher-dimensional information with different effective radii expressed at different scales of measuring information on the surface. Once again, we do find quantization everywhere we look, but not in a canonical way.

Emergence of Quanta

When solving wave equations, we make use of apparently magical techniques like Perturbation to pull analytic results out of what should have no solution. I remember using these Perturbation techniques in my applied mathematics course and feeling as though we were doing something forbidden when we could enact a bound on error at two scales of a system in such a way that, at the limit, the error could disappear (or at least become arbitrarily small). Regardless, these models have proven extremely fruitful in finding mathematical models of reality. When solved, we do in fact find discrete quanta emerging from our models of the continuum. This is how we developed a theory of discrete units in Quantum Mechanics. These discretizations emerge from our solutions to wave equations is similar to how musical instruments have harmonic modes. The timbre and harmony of intervals relies on the emergent discrete resonances, yet a continuous phenomenon underlies the mechanism. This emergence of quanta from continuous models is mesmerizing to me, and lately I have been wondering if a deeper understanding of their genesis lies in the study of computability.

On Mathematics

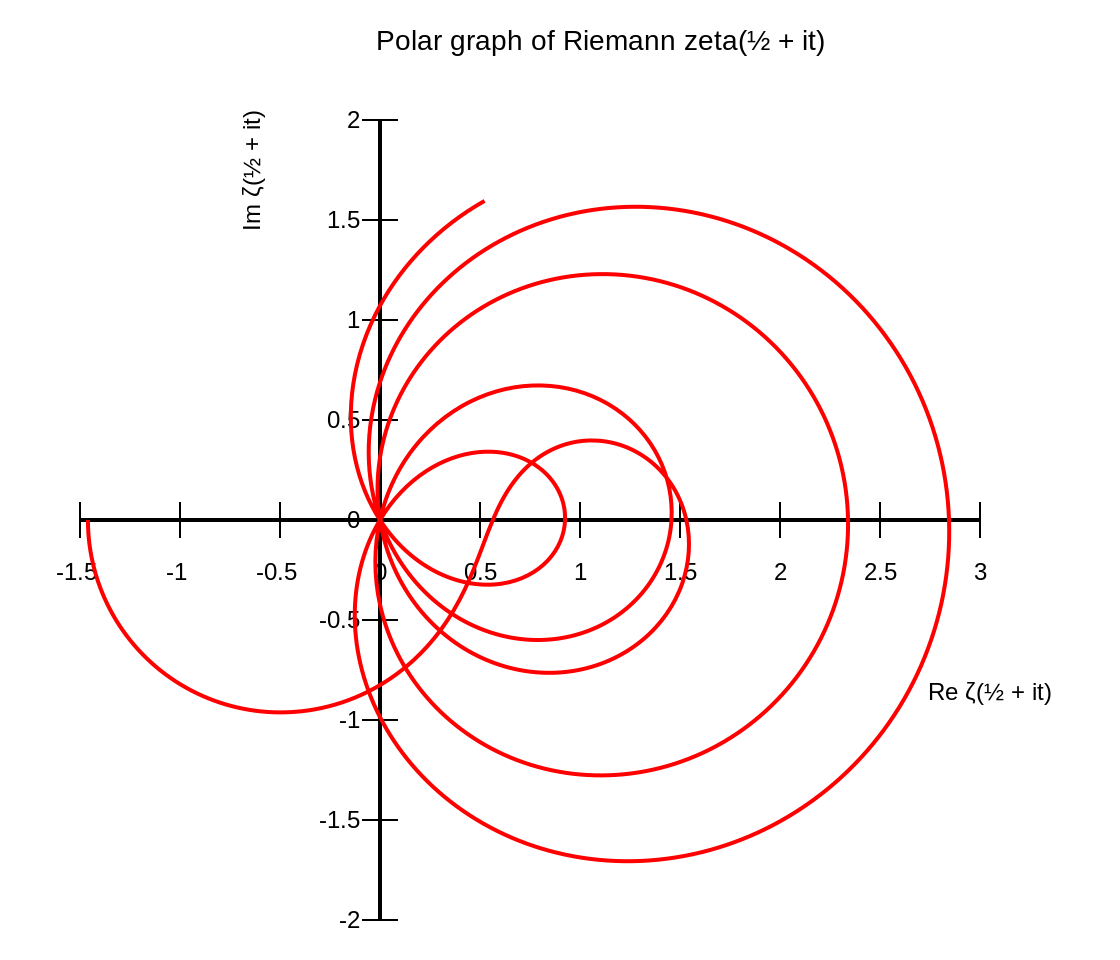

The Riemann Zeta Function, graphed (source).

The Riemann Zeta Function, graphed (source).

In a similar vein, I have always been awed and confused by the apparent divide between number theory and the other algebraic fields of mathematics. Look closely between any two regions of mathematical study and you will find numerous dualities weaving a dense web of interconnection. Yet, number theory seems to exhibit a repelling force to the rest of math. Mathematical objects such as the Riemann Hypothesis build a bridge to number theory by exploiting the periodicity of continuous functions. While I only have a cursory understanding of it, the Langlands Problem is a massive effort to construct formidable and durable machinery for answering number theoretic questions using algebraic reasoning, but it remains one of the largest pieces of active work in Mathematics today and we don’t have good answers yet.

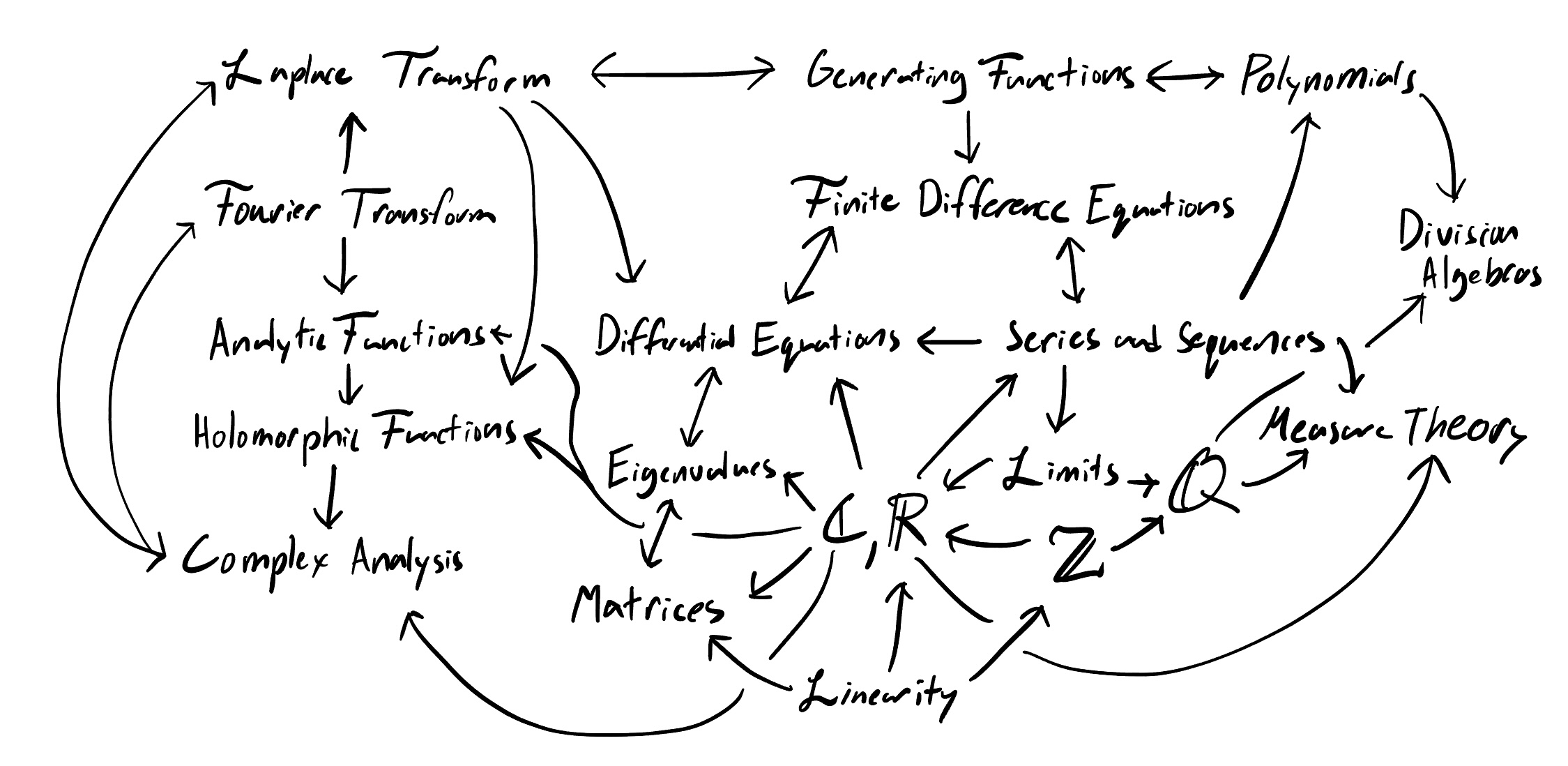

A small sample of connected concepts in algebraic regions of mathematics.

A small sample of connected concepts in algebraic regions of mathematics.

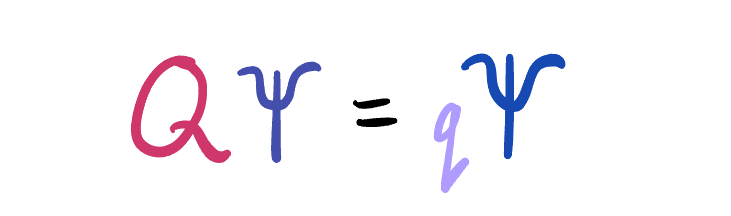

What I mean by “algebraic” is that, for much of mathematics, a little goes a long way. By defining very simple constructs such as sets and binary operations with an amount of properties you could count on one hand, we can reconcile models so powerful that they predicted the existence of Black Holes before we ever directly imaged one. These are powerful ideas, and yet, they are also elegant and convenient. Simple concepts such as Eigenvalues combined with infinite linear operators like differentials allow us to build bridges, predict quantum systems’ behavior, and even probe the dynamics of biological populations.

An eigen-operator Q acting on an object Psi yields Psi again, but scaled by a factor of q.

An eigen-operator Q acting on an object Psi yields Psi again, but scaled by a factor of q.

Yet, in number theory, simple questions such as “is every even integer greater than \(2\) the sum of two prime numbers?” have been unsolved for hundreds (and in some cases, thousands) of years. We can make clever use of Modular Arithmetic along with inductive techniques to prove results in many cases, but often it is not intuitive when a given question in number theory will be easy to solve or impossible.

Peano Arithmetic

Dominoes (source).

Dominoes (source).

What are these integers that so adeptly evade any attempt at constructing useful tools of reasoning? The most commonly used formalism to construct the integers is Peano Arithmetic. Like in the case of algebraic mathematics, we begin with some clever axioms: there exists a number \(0\), and a function \(S\) that, when fed a number, it yields the successor to that number. As \(S\) is defined from a number to a number, it may be recursed. \(1\) is representable as \(S(0)\), \(2\) as \(S(S(0))\) (and so on). These axioms also introduce a notion of equality which is reflexive (that is to say that \(x = x\)), symmetric (\(x = y \iff y = x\)), transitive \(x = y, y = z \implies x = z\) , and closed (meaning that if \(a\) is a number and \(a = b\) then \(b\) is also a number).

This is sufficient to construct all of the integers (denoted as \(\mathbb{Z}\)), but it is also sufficient to limit the capabilities of mathematics. Kurt Gödel and Alan Turing independently realized that any formal system complex enough to encode the integers (called “Recursively Enumerable”) is incapable of proving its own consistency. Such systems are also incomplete, meaning that there are statements representable within the language of the system that cannot be proven or disproven using just the system’s rules of deduction.

Church Numerals

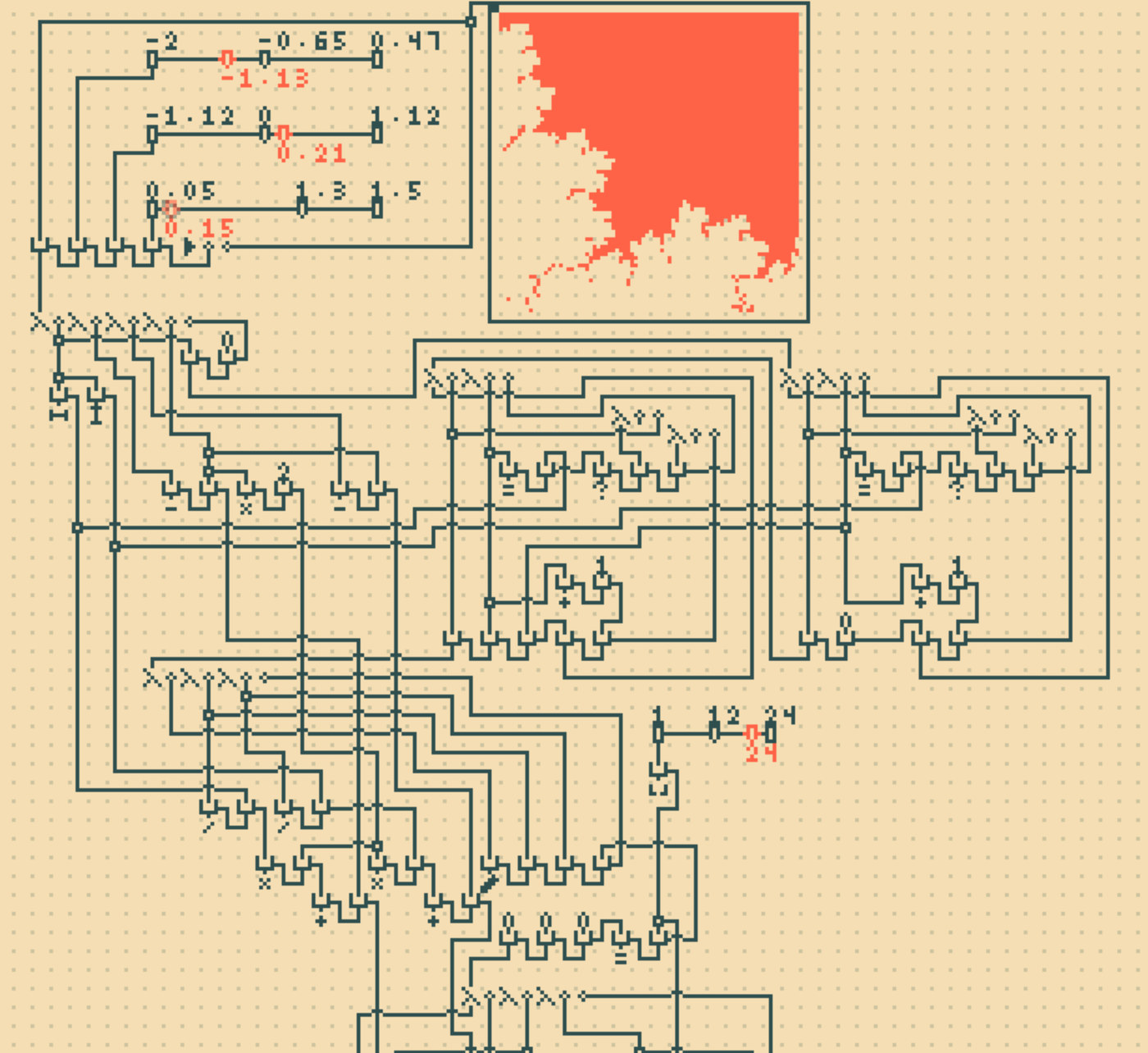

λ-2D: An artistic Lambda Calculus visual language (from Lingdong Huang).

λ-2D: An artistic Lambda Calculus visual language (from Lingdong Huang).

Around the same time, Alonzo Church had formulated Lambda Calculus, an abstract model for computation that was far more elegant and easy to reason about than that of a Turing Machine. Whereas a Turing machine expressed computation as operations over stored state with a set of instructions, Lambda Calculus took an axiomatic approach similar in spirt to Peano arithmetic.

Lambda Calculus

- There exist variables, denoted by characters or strings representing a parameter or input. For example, \(x\).

- There exists abstractions, denoted as \(\lambda x. M\) which take a value as input and return some expression \(M\) which may or may not use \(x\).

- There exists application, denoted with a space \(M N\) or “\(M\) applied to \(N\)” where both left and right-hand sides are lambda terms.

While difficult (if not impossible) to construct physically without already having some other universal model of computation like a Turing Machine, Lambda Calculus expresses the same set of algorithms that can be run on a Turing Machine (or any other universal model). It was not intuitive to me, at first, how one would use such a simple system to replicate all types of computation. After all, it was far easier as a human to reason about things like numbers, lists, trees, boolean algebra, and other useful concepts in computer science on a Turing Machine which was much closer to pen and paper than this new abstract world.

The easiest constructs to express in Lambda Calculus are, in fact, the integers. The same recursive construction used in Peano Arithmetic can be employed here with careful substitution to make the concept compatible with our new axioms. First, there exists a number \(0\) read as “\(f\) applied no times”. As you might expect, the integer \(g\) is read as “\(f\) applied \(g\) times”:

\[ 0 = \lambda f. \lambda x. x

\]

\[ 1 = \lambda f. \lambda x. f x

\]

\[ 2 = \lambda f. \lambda x. f (f x)

\]

\[ 3 = \lambda f. \lambda x. f (f (f x))

\]

Then, a successor function \(S\) can be represented as “the machinery that takes a number \(g\) and yields a new number \(g’\) that applies \(f\) one more time than \(g\)”.

\[ S = \lambda g. \lambda f. \lambda x. f(g f x) \]

I’ve used \(g\) here to denote the number instead of \(n\) because, when thinking about Lambda Calculus, it is easy to forget that everything is a function (including these numbers we are defining). \(g\) is indeed a “number”, but in this universe numbers apply operations that many times. This explanation is likely sufficient for this post, but you can take this as far as you would like and define the normal operations over integers such as addition (\(m + n = \lambda m. \lambda n. \lambda f. \lambda x. m f (n f x))\)), subtraction, and multiplication.

Church Numerals alone are a powerful construction, but repeated application is not sufficient if we wish to create a universal system equivalent to a Turing Machine. For that, we need to shim a concept of iteration called General Recursion. Ordinary recursion is fairly simple in Lambda Calculus, allowing for infinite regress as easily as \(M = \lambda f. f f\) (also known as the \(M\) combinator). When fed itself, it becomes itself.

\[ (\lambda f. f f)(\lambda f. f f) = (\lambda f. f f)(\lambda f. f f) \]

As you might guess, while a neat party trick, this does not allow us to create anything useful computationally. We need a piece of machinery that can take a function, and pass it to itself somehow. After all, if a function has access to itself then it may call itself which is our current goal. The \(M\) combinator gets us so close, we only need:

- A way of passing in a function \(f\) that (somehow) takes itself as a parameter

- Some way of terminating the infinite regress

In other words, we need a function \(Y\) that has the unique property \(Y f = f (Y f)\). This would imply that \(Y\) passes \(f\) to itself somehow, and since \(f\) is passed this value it can choose whether or not to call it (giving the option for termination). This is the famous Y Combinator:

\[ Y = \lambda f. (\lambda x. f (x x))(\lambda x. f (x x)) \]

Notice how the body of \(Y\) contains machinery that looks a lot like \(M\), except with an additional call to \(f\) along the way. A good exercise is to try and reduce \(Y f\) and to verify that it does become \(f (Y f)\). In a way, the \(Y\) combinator is the child of Church Numerals (applying a function \(g\) times) and the \(M\) combinator (self-application). The \(Y\) combinator only supports one argument, but can easily be generalized to support an arbitrary amount of arguments.

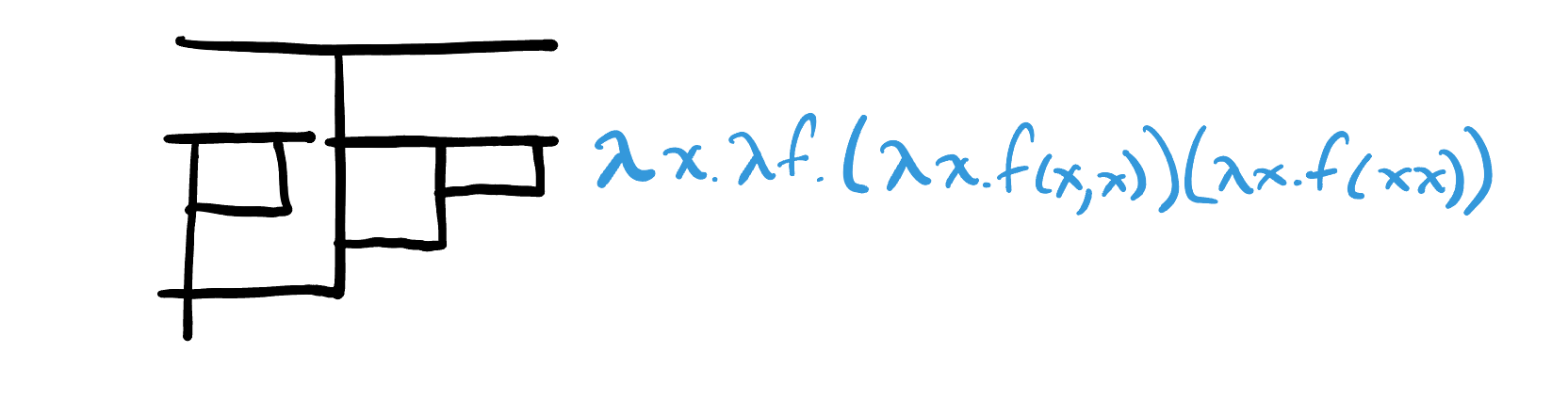

The Y Combinator expressed in John Tromp’s Lambda Diagrams.

The Y Combinator expressed in John Tromp’s Lambda Diagrams.

Type Theory

As it was the case with Peano Arithmetic and recursively enumerable formal systems leading to paradox via Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, the \(Y\) combinator also encodes a paradox. That is to say, the \(Y\) combinator can be used to construct absurd self-referential statements. Even before Lambda Calculus was studies, individuals like Bertrand Russell attempted to remedy these kinds of paradoxes with a new field of mathematics called Type Theory. Originally created to solve Russel’s Paradox (a similar inconsistency in set theory), type theory aligns well with Lambda Calculus allowing us to endow functions with a notion of parameter and return types, along with a type for the function itself. In its most basic form, typed lambda calculus operates over the type \(*\) which reads as “the set of all types” with an additional \(\rightarrow\) operator that allows you to construct functions over the types. For instance, \(* \rightarrow *\) is the type of “a function from a type to a type”.

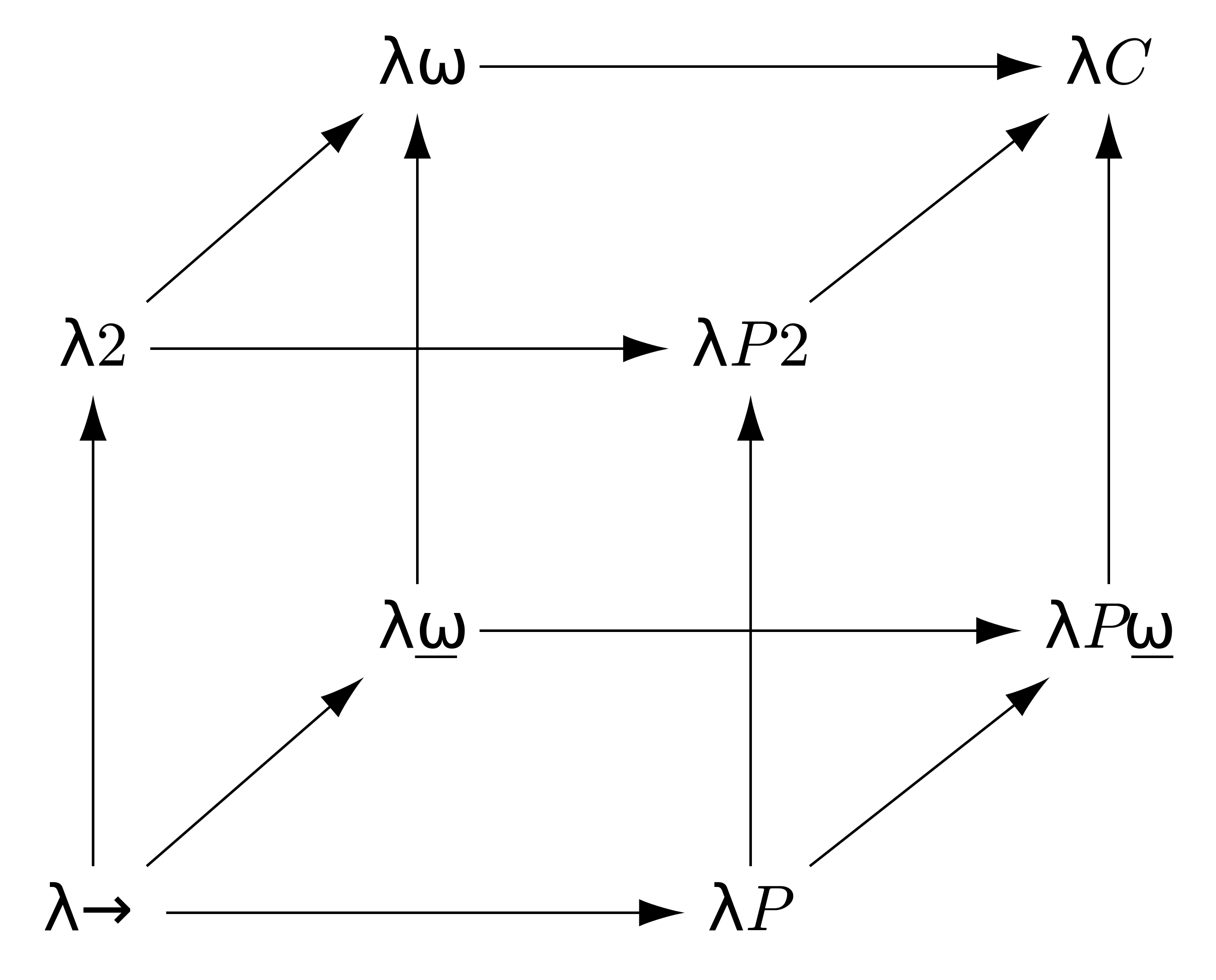

The Lambda Cube, where → indicates adding dependent types, ↑ indicates adding polymorphism, and ↗ indicates allowing type operators.) (source).

The Lambda Cube, where → indicates adding dependent types, ↑ indicates adding polymorphism, and ↗ indicates allowing type operators.) (source).

In typed Lambda Calculus, it is impossible to create the \(Y\) combinator. The same self-reference that gives it its utility results in an Achilles’ heel that results in the type signature never terminating. Still, the typed lambda calculus is incredibly useful in its own right and supports many rich operations, just not general recursion. Many extensions can be added to the types, but until you allow for something like the \(Y\) combinator these systems are all strongly normalizing (which means operations are guaranteed to terminate and not infinitely regress).

Haskell’s logo combines the lambda with a symbol ⤜ representing monadic binding.

Haskell’s logo combines the lambda with a symbol ⤜ representing monadic binding.

Second-order typed Lambda Calculus (also romantically called \(\lambda_2\)), which extends the simply typed Lambda Calculus with polymorphism, is what modern languages like Haskell are built on top of. But, if \(\lambda_2\) is only strongly normalizing and cannot express general recursion, how is it a useful programming language? We throw our hands up into the air and introduce a familiar function which is the seed that sets Haskell into motion:

fix f = f (fix f)

This is the \(Y\) combinator expressed in Haskell, where instead of relying on lambda terms we use the language’s ability to allow functions to reference themselves in their definitions. This is not as elegant as the \(Y\) combinator, but just as powerful and it means that many properties about languages like Haskell are actually Undecidable (behaving just like the systems discussed in Gödel’s proofs).

Curry-Howard Isomorphism

In studying Lambda Calculus, Church and others recognized a surprising and profound correspondence between computation and mathematics. They found that the abstraction, application, and reduction of terms in Lambda Calculus were not only capable of representing mathematical proofs, they were functionally equivalent. This remarkable duality comes from thinking about the type of a lambda term as the formula it proves and the proof as executing the program. The formula is then true if the evaluation terminates.

As a caveat, this only works in general for provably finite algorithms (as is the case in strongly normalizing languages), otherwise we run into Turing’s Halting Problem. This subset of mathematics is called Intuitionist Logic and prohibits the use of The Law of Excluded Middle in evaluating proofs (which consequently bars double-negation as well). The mathematics we commonly use allow for these concepts instead of forbidding them (like in ZFC).

When proving the correspondence, it is far more convenient to use SKI Calculus rather than raw Lambda Calculus. As in the case with physical computational models of Turing Machines, there are many equivalent formulations that produce the result we want. A computer may be constructed from NOR, NAND, or other combinations of gates and still have the same emergent properties. SKI calculus introduces three combinators that can be used to construct any Lambda expression:

- \(S = \lambda x. \lambda y. \lambda z. xz(yz) \rightarrow\) substitution

- \(K = \lambda x. \lambda y. x \rightarrow\) truth

- \(I = \lambda x. x \rightarrow\) identity

The \(S\) combinator in particular is difficult to understand at first, but it represents a concept known as Modus Ponens in propositional logic. This is the step in theorem proving when you apply some piece of knowledge you have to an expression you already have. A very simple example is that the identity combinator \(I\) can be “proven” by applying the \(S\) to \(K\) twice (\(I = (S K) K\)). As usual, propositional logic proves difficult to follow but the key takeaway is that \(S\) and \(K\) represent the most fundamental operations in theorem proving, identifying that all proofs are actually programs.

This was a watershed moment in the intersection of mathematics and computer science, allowing for mathematical theorem proving software. In particular, a specific typed lambda calculus \(\lambda_C\) that allows for both dependent typing and type operators in addition to the polymorphism of \(\lambda_2\) is the basis of the Coq theorem proving software. As you may have inferred, Coq is not a Turing Complete language but is still remarkably useful when we want to computationally verify mathematical proofs.

On The Canonical Existence of Integers

Ripples on an alpine lake.

Ripples on an alpine lake.

Where does this leave us with our questions about the emergence of quanta in our models of physics? Lately I have been allowing myself to think more intuitively about these things, while attempting to remind myself that this is a form of play. If you will indulge me in this exploration, I would love to share the thoughts I have had so far (however incomplete they may be). My writing up to this point has mostly covered a reflection of what we currently know, so this marks a transition into my own reflection and opinions on where things may be headed in our understanding of the world.

I believe an equivalent and perhaps more formal rephrasing the question of the emergence of quantiztion would be “Do discrete entities canonically exist, and if they don’t, when, where, and by what means do they emerge?”. While reading David Tong’s essay, one sentence especially stood out to me:

The integers appear on the right-hand side only when we solve [the Schrödinger Equation].

Could it really be the case that integers are an artifact of a computational understanding of reality? If we are to interpret the Church-Turing Thesis literally, then all forms of computation are equivalent inasmuch as an algorithm for one universal machine may run on any of them if written in the language of the other machine. Turing Machines, Kolmogorov Machines, Lambda Calculus, Cellular Automata, Quantum Circuits, Adiabatic Quantum Computation, Large Language Models, and even models inspired and modeled after the brain like Neuromorphic Engineering are all universally equivalent. Quantum models of course offer additional efficiency in time complexity, allowing for operations like factoring integers asymptotically faster than a classical computer, but they still operate on the same space of algorithms. There is no algorithm that is computable in a quantum computer that is not computable in a classical one.

If computation is really something more fundamental; an operation on information itself (as is the case in Constructor Theory), and we are another complex form of computation, would a computational understanding of our world be the only possible one we could understand? We may observe the continuum and all of its complex interactions, but we must measure it in order to have any information to draw conclusions from. What if the process of measurement is a form of computation on correllated entangled particles, akin to the emerging hypothesis of Quantum Darwinism?

And what about the mathematics of the continuum? One may argue that analysis makes the notion of a continuum formal, but I wonder if we are simply shimming our computationally discrete scaffolding onto our observations of the world. We often construct the continuum in a discrete way, beginning with a finite case and using some concept of an infinite process to yield a limiting behavior, Zeno-style. As is the case with our other systems, this is wildly successful and has yielded extensions of our algebras over infinite objects, but at its core is it really a reflection of the truth (if there is such a thing)? Gödel, a platonist, believed that statements like the Continuum Hypothesis could be false even though they are independent (or, undecidable) in our constructions of mathematics (ZFC or ZFC+, in this case).

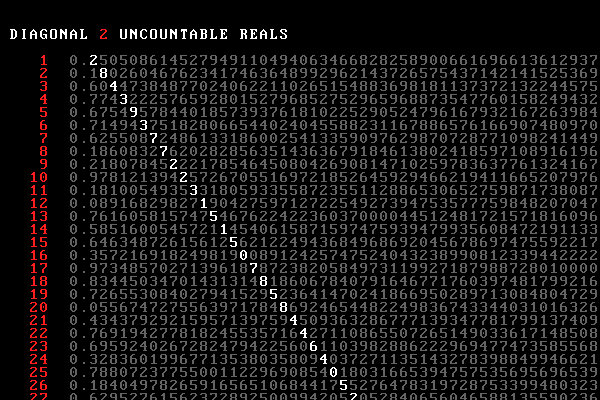

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, Turing’s Halting Problem, Cantor’s Theorem on the uncountability of the reals, Russel’s Paradox in set theory, the Y Combinator of Lambda Calculus, and the incompatibility of Kolmogorov Complexity in computational information theory are all reflections of an abstract form of reasoning called a Diagonalization Argument. It seems that everywhere we find systems capable of self-reference, inconsistency follows as a direct conclusion. Something akin to integers arises in all of these cases (Zermelo Ordinals, for instance), and in the case of strongly normalizing systems like typed Lambda Calculi without general recursion you can still formalize the notion of a successor and express finite integers.

Cantor’s Diagonal Argument from Max Cooper’s music video for his track Aleph 2

Cantor’s Diagonal Argument from Max Cooper’s music video for his track Aleph 2

To me, it seems natural to accept that our reality is fundamentally continuous in some way. Wave-like phenomenon exhibit periodicity, which is a kind of temporal quantization, but not in any canonical way. In the same way that we have stared in vain at the structure of the prime numbers for thousands of years unable to explain their structure, yet freely admitting that they have it, I wonder if a search for a theory of everything in physics may prove fruitless. By all means, this does not mean that we should stop, but as in the case of Principia Mathematica being motivated by trying to axiomatically derive all of mathematics only to be proven impossible to do by Gödel, maybe we need to re-think our approach and start thinking outside of our systems to see what they are actually capable of.

Somewhere amidst the swirl of equivalent systems masquerading as independent entities, we may find a unifying pattern that is representative of the space of understandings that humans (and conscious entities) can possibly have. At the other side of that endeavor, we may stare into the mesmerizing patterns in an orchard that connect to so many things and find what we see to be an abstract reflection of ourselves, and us a reflection of it.

Afterward

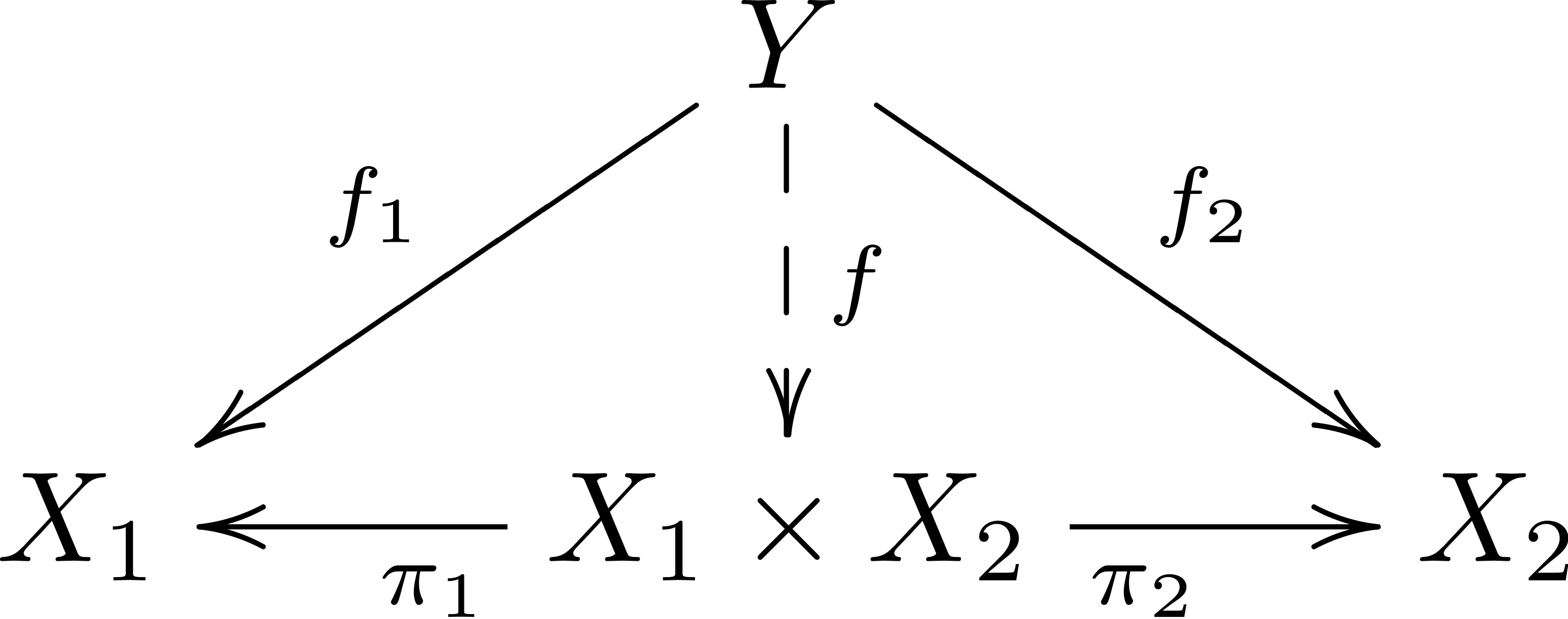

I’m so interested to find an answer to the question: “what is the canonical model for computation?”. I hope that, in finding this answer, we might inch closer to understanding the connection between all of these systems. Category Theory seems uniquely poised to approach this problem, and (maybe not so) coincidentally has already fueled a theory of how to make Lambda Calculus practical. It is a system of mathematics adept at looking at numerous instances of similar operations and finding the skeleton underlying them all. A popular example is the categorical product which (at first glance) seems miraculous and impossible for anyone to be so clever as to come up with it in a vacuum. That would be correct, as Category Theory is more of a meta-study of mathematics and structure itself. At times, it feels more empirical than deductive, but it is no less effective as a mathematical vehicle for truth as any other field.

A diagram conveying the Categorical Product.

A diagram conveying the Categorical Product.

At its heart, Category Theory seeks to find “the most general” form for a given abstraction, which often takes the form of a Universal Property. It reminds me of Hamiltonian and Lagrangian mechanics where a system can be fully characterized by its desire to be in the minimal state of some measure (energy, in the case of the Hamiltonian). Something about the fundamental behavior of our universe seeks to find the shortest path to the lowest point of any space. If information is truly physical, and it very well could be (remember that the Bekenstein Bound lies at the heart of the holographic principle), it might make sense how so many of our most powerful results in math are the most elegant ones. In my last post, I talked about how information compression is analogous to artificial intelligence. Maybe the most abstract form of computation comes as a dimensionality minimization attempting to find the latent manifold information truly lies on. This kind of mechanism would be biologically adventitious as it would yield compact and efficient representations of incoming information that would be highly correlated with the global information landscape an individual was embedded in. Will our search for a canonical model for computation merge with our attempt to understand intelligence?

Where Category Theory could potentially reconcile a concrete understanding from all of this hand waving by characterizing the ingredients of such a system. This would hopefully make it more obvious where to search for how such systems physically manifest themselves in our universe.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.