Mathematical Blind Spots

All too many times in our educational paths the answer to curious inquiry is tautological: Why does it work that way? Because that is the way it has always been done, or at least the one we stuck with. One of the many reasons many fall in love with Mathematics is that, more often than not, you are afforded the liberty to further question that class of answer and find deeper meaning where you may not expect it. There are certainly limits to this inquiry, the foundation of Mathematics relies on axiomatic assumptions after all. Still, modern Mathematical education is fraught with these sorts of answers and much can be learned by being stubborn and persisting until you find the real answers.

An Embarrassing Question

Every once in a while, it is fun to go back over the things you have learned and identify gaps in your understanding. One day when I was thinking about my early Mathematics classes, I realized that a piece of my understanding was based on assumption and that I possessed no intuition on: the relationship between radians and trigonometric functions. Why are Radians the natural choice as arguments to trigonometric functions? And how does the geometric intuition of the Unit Circle relate to the Taylor Series representation of \(\cos\) and \(\sin\)?

At first, I felt kind of embarrassed. We are all at different points in our journey in Mathematics, but this is something I learned over ten years ago. Surely the answer must be obvious, and I must have forgotten it. I asked some of my Math friends to see if they knew the answer, and also searched the internet to see what I expected to be a quick answer and resolution to my question. To my surprise, finding the answer took me on a journey and taught me a valuable lesson about our assumptions when we study Mathematics.

Now, I know what you may be thinking: Radians are obvious! What are you missing? If you don’t use radians, you have to carry around extra terms whenever you do math involving trigonometry. Who wants to use \(\cos(\frac{\pi \theta}{180})\) when you could just use \(\cos(\theta)\)? That much is very clear: Whatever the reason, when you use Radians the Math just turns out cleaner.

Everywhere I asked, and most places I found online the answers generally fell into a few common categories:

- Radians are defined such that \(2 \pi\) radians is a full revolution, it’s the arc length of the unit circle.

- We use Radians because notationally it is a lot simpler. Otherwise you would have to carry around constant terms.

- Radians are unitless, that’s why they work.

- The limit \(\lim_{x\rightarrow\infty} \frac{\sin(x)}{x} = 1\) only works if \(x\) is in radians.

Across all of these answers, there was a common theme I was noticing. For one, people were confident that they understood how this worked. Also, although my friends were often very kind in their response, in online forums there was a varying but ever-present degree of incredulity that such a basic question was being asked. I’m sad to admit that at many times during my search, I considered abandoning my line of questioning all-together since it seemed like the answer was both beyond my understanding and yet so simple that it attracted judgement for having asked for it at all. Still, I was not satisfied with any of the answers I had received so far. Worse yet, I was finding it difficult to articulate why these answers weren’t satisfying. Clearly the confidence of those giving answers meant that they were satisfied with their own understanding, why couldn’t I be?

It boiled down to another common theme among all the questions I had received so far: they all relied on some amount of tautological reasoning: “it is what it is”. Claiming that we define radians to be the angle is orthogonal to the question: why \(2 \pi\)? Why not 69? If the answer to my question truly is “we define it”, then why don’t other definitions work just as well? The argument from notation was even weaker: It would be like asking the question “Why do we use an internal combustion engine for most cars?” and receiving the answer “Because bike pedals would be too difficult.”. Notation is rarely the source of truth, rather it is usually a reflection of it. The reason not using radians results in extra constants is not a choice we made. Likewise, the argument from units also deftly circumnavigated giving an answer at all. Sure, radians are unitless, but like the argument from definition it provides no explanation for why trig functions’ diet consists of them. Lastly, the argument regarding limits came closest to a real answer, but I generally saw no further elaboration as to why these limits would not work with degrees, or any other measure of angle. When justification was provided, the proofs started by defining radians to start at \( 0 \) and end at \( 2 \pi \), some even defining \( cos \) and \( sin \) to take radians as arguments. While this may lead to valid conclusion, at some point along the way we avoid answering the question “Why was this definition chosen?”.

Resolution

If you’re with me in not being satisfied with the answers so far, then fear not! It turns out that there is a real reason behind the choice of radians for trigonometry (and the answer is beautiful). Today I took another look at Tristan Needham’s wondrous textbook Visual Complex Analysis and (at last) found a satisfying answer to my question. Before I go through the proof, though, I wish to conclude my venting about Mathematics education and the lesson I learned.

This isn’t the first time this has happened, and I’m fairly certain (and honestly hopeful) that it will not be the last. I remember fondly in my early physics courses feeling intense satisfaction at the intuition behind all of the math we had employed. My happiness turned to confusion when we began talking about electromagnetism, and specifically the magnetic field. What was this magic field that could augment electrical forces? Where did it come from, and why does it spiral about the movement of electrons? The answer my professor gave at the time was something along the lines of “that is just how we define it”, but the next day I was surprised to see that my professor’s answer had changed. He had gone home and read more on electromagnetic theory. That day we had a great conversation where he explained that magnetism is actually a side-effect of Special Relativity and that the magnetic field is something we invented to keep track of those effects. I will always be inspired by what my professor did, and the journey we went on as we questioned pieces of knowledge that are often just passed along in school without justification. I would go so far as to say that was the highlight of that entire semester.

If the answers we find when we examine our blind spots end in clarity and excitement, why do we avoid them? At the very least, why aren’t we encouraging of others when they seek to further their understanding (even if we are satisfied not knowing ourselves)? I think a part of the answer lies in Mathematics education generally relying on rote memorization and algorithmic application. It saddens me, but perhaps the problem lies in the general sentiment that Mathematics is a subject of acceptance, not of understanding. Other subjects truly do have this problem, but Mathematics is constructed. The deductive nature of theorems means that most questions you can ask have an answer, and the rare cases where there isn’t an answer are even more fascinating.

If I’ve learned anything from this experience it is to never discount a question on the basis of the level it is asked. I have to imagine that all levels of knowledge are similarly likely to contain blind spots, and clearly the level of the question has little bearing on how exciting the answer will be. Also, I need to learn to be more skeptical of my understanding. There is nothing to be learned when we perceive that our understanding is complete.

The Proof

For full effect, please please please find a copy of Visual Complex Analysis if you (like me) are a fan of satisfying geometric intuition for mathematics, then this book is a goldmine of gorgeous proofs and durable understanding of topics that take much more time to master without a visual intuition. This proof begins on page 10 of the book. I’ll do my best to provide my own transcription of the proof here.

To no surprise, the intuition comes easiest from the viewpoint of Complex Analysis, one of the most ironically named subjects in all of Mathematics (as it is full of some of the most beautiful and understandable proofs in all of Math). If you have taken or are taking Mathematics courses at or above the level of Pre-Calculus/Calculus I then this proof should be accessible. I’ll do my best to explain the tools I use so that even if you are earlier along in your journey there will still be value here (and hopefully intuition).

To begin, we will examine Euler’s Formula: A cornerstone of Mathematics by my favorite mathematician. It goes like this (this is a claim to be proven):

\[ e^{i\theta} = \cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta) \]

where \( i \) is the imaginary unit and \( e \) is Euler’s number. \(e \) is chosen as the base of the exponent \(e^x\) because the rate at which \(e^x\) increases in value is equal to itself at all times. Wonderfully enough, when you feed the exponential function imaginary numbers it begins to rotate in the complex plane. More precisely, the complex point \(e^{i\theta}\) is the point of distance \(1\) from the origin lying along the unit circle at angle \( \theta \) in the complex plane (and we will justify this):

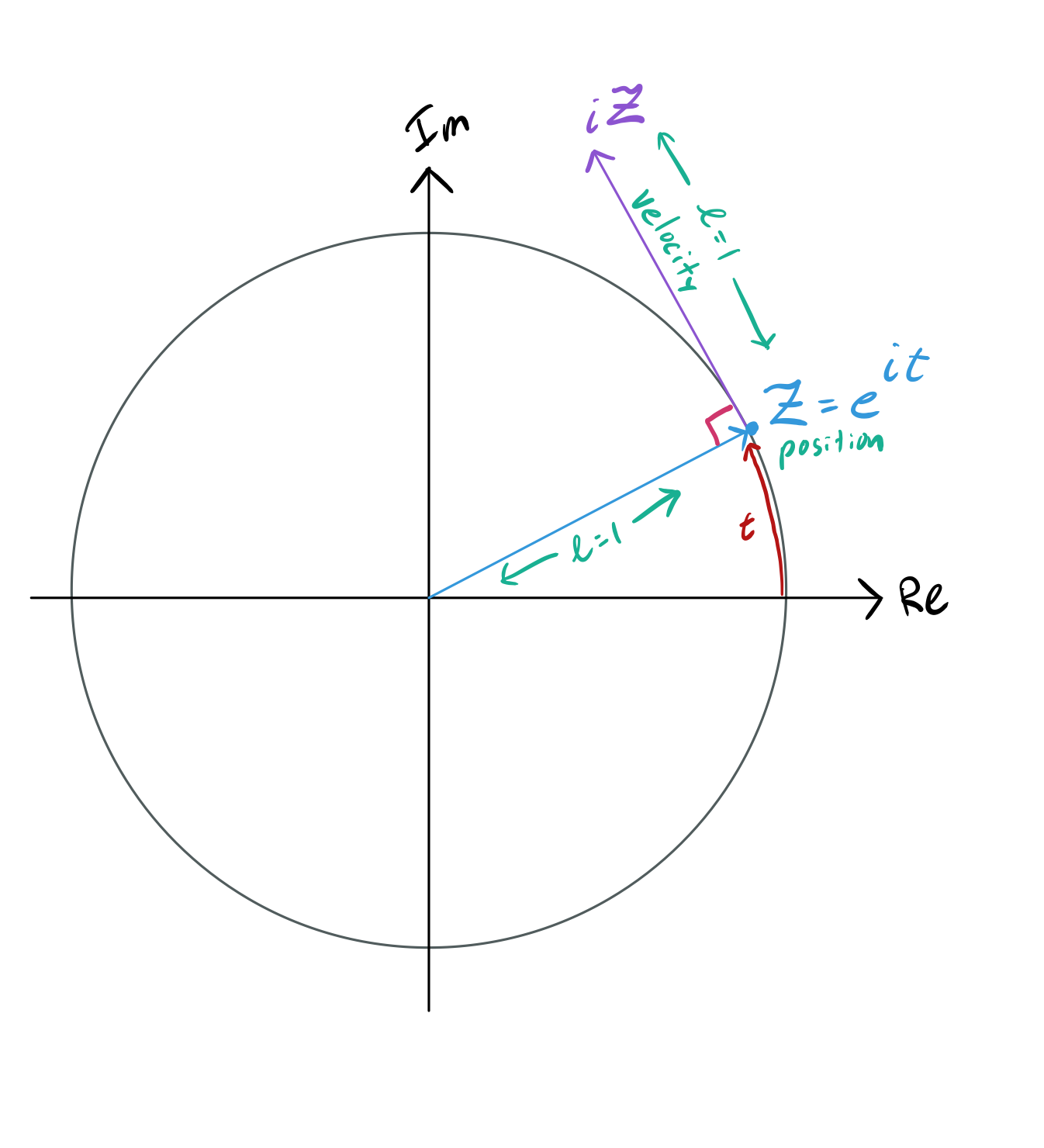

Recall that the derivative is an operator that determines the rate of change of a given function with respect to its input. For a moment, instead of assuming that the argument to Euler’s Formula is an angle, let’s instead pretend that it is time. The derivative in this case now becomes velocity. In the world of complex numbers, this velocity has a direction (whereas in real numbers it would just be a single number). We can easily enough find the derivative of our complex exponential function:

\[ \frac{d}{dt} e^{i t} = ie^{i t} \]

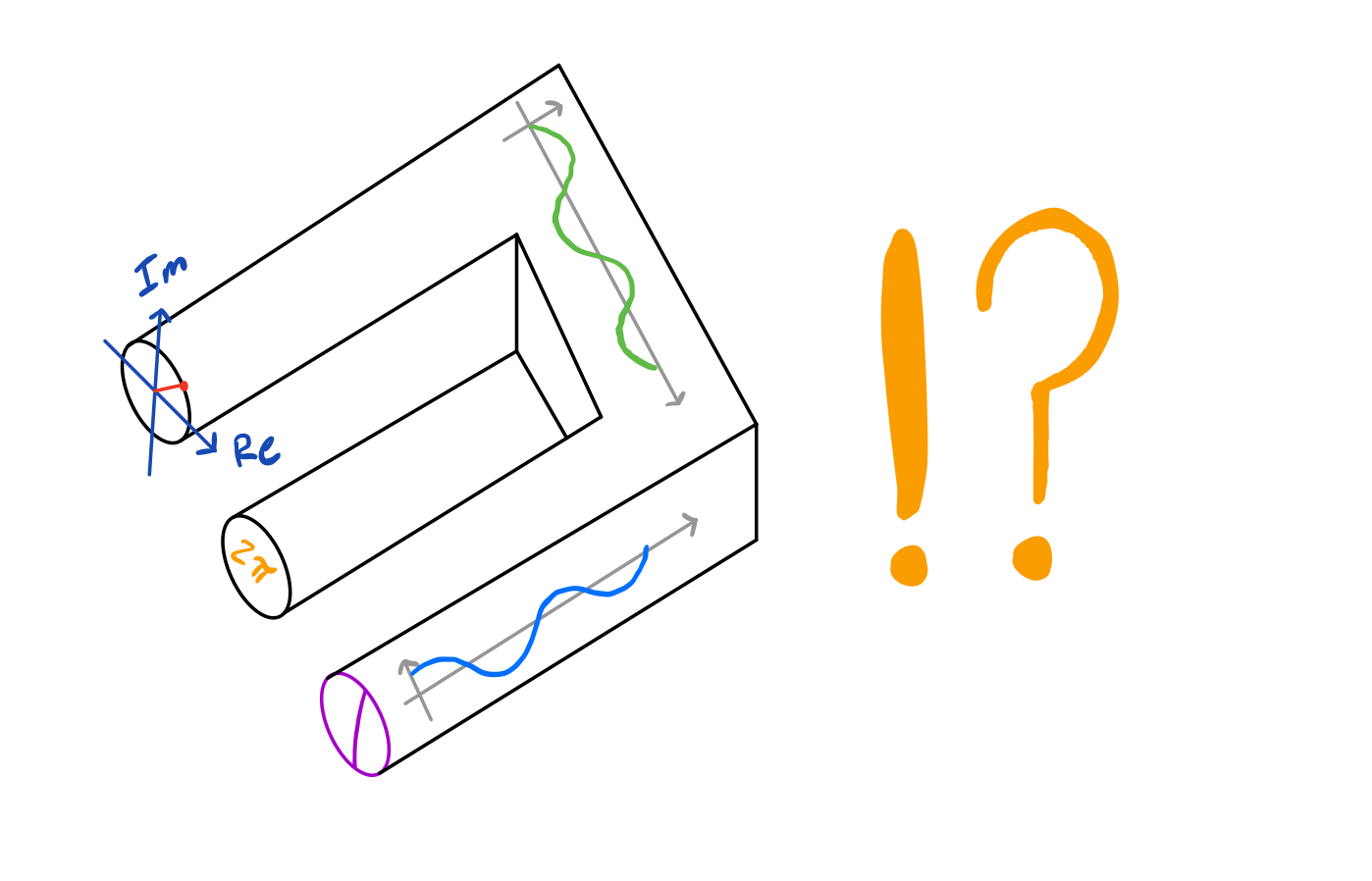

This means that for any point along the trajectory of our complex exponential \( Z = e^{i t} \) the velocity will simply be \( iZ \). As multiplication by \( i \) is just rotation of our position through a right angle, and our position is always equidistant to the origin, our velocity will be unchanging and at a right angle to our position from the origin. The only trajectory where this construction is valid is a circle. The key insight here is that as our position is always of distance \( 1 \) from the origin, our velocity is also \( 1 \) unit per second. This means that after \(2 \pi \) seconds, we will have travelled a full revolution around the circle (because this is the circumference of a circle of radius \( 1 \)).

But where do \(\cos\) and \(\sin\) come into play? It may seem obvious from the standard construction of the unit circle where the horizontal and vertical positions of any points are \(\cos\) and \(\sin\) respectively, but that would be jumping the gun. Yes, both our complex exponential and the trigonometric view of the unit circle trace the same paths, but we have no justification yet that they are one and the same. Fundamentally, we still have no intuition for what \( \theta \) is when fed to \(\cos\) and \(\sin\); we don’t have justification that both paths are traced at the same rate (at least not yet). And, most certainly, we cannot simply define away ambiguity at this point.

Instead, we turn to another incredibly useful mathematical tool: the Taylor Series. Many functions can be represented as an infinite sum of higher and higher powers of an input variable. The convergence of these series is miraculous, and they allow us to study functions in ways that would be impossible otherwise. Here are three useful Taylor Series that will be helpful to us:

\[ \cos(x) = \displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^{2n}(-1)^{n}}{2n!} = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^4}{24} + \cdots \] \[ \sin(x) = \displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^{2n + 1}(-1)^n}{(2n + 1)!} = x - \frac{x^3}{6} + \frac{x^5}{120} + \cdots \] \[ e^x = \displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^n}{n!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{6} + \frac{x^4}{24} + \cdots \]

Note that the Taylor Series for \(\sin(x)\) consists of odd exponent terms with alternating signs, \(\cos(x)\) consists of even exponent terms with alternating signs, and \(e^x\) consists of all terms with no alternating signs. What happens if we feed the exponential a complex argument?

\[ e^{ix} = \displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(ix)^n}{n!} = 1 + ix - \frac{x^2}{2} - i\frac{x^3}{6} + \frac{x^4}{24} + \cdots \]

You may notice the pattern: odd terms remain imaginary, and even terms are real. Among odd terms, the sign alternates each time. Among even terms, the sign also alternates. If you separate the real and imaginary parts of this infinite sum, you get:

\[ e^{ix} = C(x) + iS(x) \]

where

\[ C(x) = \displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^{2n}(-1)^{n}}{2n!} = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^4}{24} + \cdots \] \[ S(x) = \displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^{2n + 1}(-1)^n}{(2n + 1)!} = x - \frac{x^3}{6} + \frac{x^5}{120} + \cdots \]

These are equivalent to the Taylor Series representations of \(\cos\) and \(\sin\)! This alone is sufficient justification of Euler’s Formula, but that isn’t what we set out to gain intuition on. We can go further and ask the question: what is \(x\) in this case? We already know the answer: it must be \(\theta\), and \(\theta\) must be in radians, but why?

Let’s abandon our assumption and knowledge that the argument to \(\cos\) and \(\sin\) is an angle in radians for a moment and see if we can derive this fact from first principles. This begins with abandoning the assumption that \( C(x) = \cos(x) \) and \( S(x) = \sin(x) \). We want this to be true, but can we prove it? We can start by observing a useful property of the real and imaginary parts of the Taylor Series representation of our complex exponential:

\[ \frac{d}{dx} C(x) = \frac{d}{dx} 1 - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^4}{24} + \cdots = -x + \frac{x^3}{6} + \cdots = -S(x) \] \[ \frac{d}{dx} S(x) = \frac{d}{dx} x - \frac{x^3}{6} + \frac{x^5}{120}+ \cdots = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2} + \cdots = C(x) \]

or, more compactly:

\[ C’ = -S \] \[ S’ = C \]

where the apostrophe represents the derivative. Since the real and imaginary parts of a complex numbers form the sides of a right triangle whose hypotenuse is the segment between that point and the origin, the magnitude (denoted as absolute value) of our complex exponential \( e^{ix} = C(x) + iS(x) \) is represented geometrically using the Pythagorean Theorem as \( \sqrt{C^2 + S^2} \). We wish to show that the length of our complex exponential is constant and of unit length. This is to say that the length does not change, and consequently the square of the length would not either (we take the square as it is easier to differentiate):

\[ \frac{d}{dx} \mid e^{ix} \mid ^2 = \frac{d}{dx} (C^2 + S^2) = 2(CC’ + SS’) = 2(CC’ - C’C) = 0 \]

As \( e^{i 0} = 1 \), and the length is unchanging, the magnitude of our complex exponential is always \( 1 \).

All that is left to prove is that \(e^{ix}\) has an angle of \(x\) when represented in polar form. Let \(\theta(x)\) denote the angle of \(e^{ix}\) in the complex plane. We want to show that \(\theta(x) = x\). There are likely many ways to do this, but I appreciate the way Needham chose in his textbook. Since \(\theta(x)\) is an angle, we can examine its tangent:

\[ \tan(\theta(x)) = \frac{S(x)}{C(x)} \]

For reasons you will soon see, it is useful to consider the derivative of either side of this expression (read here for further explanation of this derivative):

\[ \frac{d}{dx} \tan(\theta(x)) = (1 + \tan^2(\theta))\theta’ = (1 + \frac{S^2}{C^2})\theta’ \]

then, recalling from our previous proof that \( C^2 + S^2 = 1 \):

\[ (1 + \frac{S^2}{C^2})\theta’ = (1 + \frac{1 - C^2}{C^2})\theta’ = (1 + \frac{1}{C^2} - \frac{C^2}{C^2})\theta’ = \frac{\theta’}{C^2} \]

Taking the derivative of the RHS instead, we find:

\[ \frac{d}{dx} \frac{S(x)}{C(x)} = \frac{CS’ - SC’}{C^2} = \frac{C^2 + S^2}{C^2} = \frac{1}{C^2} \]

Both RHS and LHS being equal, this means that:

\[ \frac{\theta’}{C^2} = \frac{1}{C^2} \]

which leaves only one conclusion: \( \theta’ = 1 \)! This means that via integration \( \theta = x + \gamma \) where \(\gamma\) is some arbitrary constant. Since \( e^{i 0} = 1\) has an angle of \( 0 \) to the real axis, this means that \(\gamma\) must be \(0\) and consequently that \( \theta = x \) (the angle of our complex exponential and its argument are one and the same!).

If we take \(x\) to be time again, recall that we travel a distance along the circle equal to the time taken. Since we now know that this time is also equivalent to the angle (as it is the argument), we can finally conclude (with confidence!) that the argument to the complex exponential is an angle measured from \(0\) at the start to \(2 \pi\) at the end. Also, as \( cos \) and \( sin \) are the horizontal and vertical components of a right triangle with unitary hypotenuse, we have also confirmed that they are indeed the real and imaginary parts of our complex exponential and its power series representation \( C(x) + iS(x) = \cos(x) + i\sin(x) \).

Again, this proof was taken from Tristan Needham’s book Visual Complex Analysis. It provided a more than adequate answer to my long-standing question about radians, but beyond that I will recommend that you pick up a copy if you enjoyed any of this proof (or my rough retelling of it, at least). I hope that it provided you some satisfaction as it did for me. Whenever you have the time, go down rabbit holes trying to patch up your own understanding. You never know what interesting links you will find.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.